Fear & Loathing at

Klondyke Corner

A report from the epic 1992 Speight's Coast to Coast multisport endurance race for NZ Adventure magazine.

In 1992 I went south to cover the Speight's Coast to Coast for Adventure magazine. It was on this trip I met my life-long friend, the adventure photographer Gareth Eyres and also the legendary mountaineer and outdoor journalist Bob McKerrow. We chased the race competitors across the South Island from the luxury of a Maui campervan. We thought we were covering a multisports event — but it quickly turned into a major news story as the weather turned ugly and people needed rescuing from the mountains. While chaos was ensuring half-way through the race I noticed Coast to Coast race director Robin Judkins leaping about in the rain barking instructions through a megaphone, giggling to himself with glee.

That was how how I introduced the story.

Exhausted and possibly hyperthermic competitors are treated by the Red Cross at Klondyke Corner after the first day of the 1992 Coast to Coast event was king-hit by a rain storm in the mountains above Arthurs Pass.

The Speight's Coast to Coast (now the Kathmandu Coast to Coast) is structured in two main divisions:

- Two Day: Competitors race over a 243km course course over two days, with an overnight camp at Klondyke Corner after the 30km mountain run stage. The two-day race is further divided into individual, team, age-group, and specialist categories. The race crosses the South Island from Kumara Beach on the West Coast to New Brighton beach in Christchurch.

- One Day (The Longest Day): Individuals (and limited 3-person teams) complete the same 243km course in a single day.

- In both divisions the race begins with a 3km run from Kumara Beach on the Tasman Sea, followed by a 55km cycle up State Highway 73. The next segment of the race is a 30km run up the Deception River, over Goat Pass and then down the Mingha River to the Bealey River rejoining SH73 at Klondyke Corner. For the two-day event, competitors overnight here. From Klondyke there follows a 15km cycle to Mount White bridge and a short 1.5km run down to the Waimakariri river to start the 70km kayak paddle to Gorge Bridge where they transition for the final 70km cycle into Christchurch.

The giggling leprechaun leapt about in the rain beneath a bright rainbow that arced across the river flats at Klondyke Corner. He turned, made a rude one-fingered gesture and then sauntered back through the wet tussock. It was a set up for the television news. The camera crew thanked him for the scene and then the Speight's Coast to Coast race owner and director flew off in a waiting helicopter to make sure no-one stole his pot of gold.

Judkins was heading for Goat Pass where the shit was hitting the fan. The front-runners of the two-day division of the trans-island multisport race had arrived unscathed but reports were coming in of tail-enders being caught in a rampaging torrent.

Down at Klondyke Corner the hounds of the press could smell blood and began to hunt in a pack. With ears well-tuned to the sound of helicopters working in anger we shrugged off our amiable sports reporter guises and went into hard news mode.

Rain was sheeting down. There was talk of real drama up the Mingha. Of floods. Of hypothermia. Of rescues. Of heroes.

As another 80 knot wind bullet lashed across the flats rocking caravans and plucking out tents the 1992 Speight's Coast to Coast changed its mode too.

The event was eclipsing the race.

There was a story here. Results became of minor importance. What we needed was a body count.

But let us backtrack to two hours earlier where — through the steamed-up window of the public bar of the Otira Hotel — there appeared a dripping wet face. We beckoned John Howard to come in from the storm .

A severe storm was lashing the western side of the Arthur's Pass route across the Southern Alps.

The 283km two-day Coast to Coast race had started at Kumara Beach at day-break that morning.

McKerrow, photographer Gareth Eyres and I were covering the event for both Adventure magazine and a soon-to-be-published book on the history of the Coast to Coast by McKerrow and publisher John Woods.

We were here also as support crew for the boss — Adventure magazine editor John Woods — who we had dispatched into the wilds of Deception Valley at the first cycle-run transition before seeking refuge from the steadily increasing rain at the first pub we found on the road over the pass.

We were relaxing in the warm hospitality of the bar. Woods was grunting and grovelling somewhere in the raincloud-shrouded mountains to our north. Maybe we would be there to offer a dry towel at Klondyke, maybe we wouldn't — such is the power of the support crew.

John Howard, individual winner of the 1984 Coast to Coast and teams winner the following year, took off his dripping raincoat and joined our table.

For Bob McKerrow, busy collecting information and interviews for a book on the history of the Coast to Coast, Howard's appearance was a godsend.

Coast to Coast promotor Robin Judkins was in his element marshalling anyone who would listen as his beloved Coast to Coast event turned to chaos after a rain storm lashed the two-day competitors making their way over Goat Pass

McKerrow bought another jug and a lemonade for non-drinking Howard, pulled out his tape recorder and ordered hot chips. it seemed a good time to talk about black bushman's singlets and Buller gumboots.

In Howard's day, so it seems, the Coast to Coast race belonged to mountain men and mountain women. These were real mountaineers and trampers who pulled on their gumboots, woollen singlets, strapped on pack-frames and headed out to cross the island by hook or by crook in canvas canoes and on borrowed bicycles.

It was in 1986 that things changed, when the triathletes began to take the event over. City-folk in their lycra cycling shorts and polypropylene t-shirts quaffing Steinlager and sipping herbal tea. "Yuppies", most of them, I was led to believe.

We got soaking wet running from the pub to our parked campervan. I cast an eye north towards Deception, somewhere above the rain and mist. There would be a few cold yuppies up there today I thought, including photographer Eyres who had flown by helicopter into the same mountains with helicopter pilot Bill Black and was probably wrecking his cameras up on Goat Pass in the rain.

I learned later that Gareth had put his camera gear aside and had helped pilot Black with a number of rescues, including guiding an exhausted Lady Hadley (wife of Sir Richard) across a swollen river to the safety of the helicopter. With the machine filled with competitors he waved Black away and made his own way to the top of the pass.

Mixed teams cyclist Lloyd Bathurst assumes the recovery position after the cycle from Kumara Beach to Deception, passing the two-day baton to his wife Susan who was unknowingly heading into a severe mountain storm.

After leaving the pub at Otira we arrived at Klondyle Corner where the aforementioned man on the megaphone was running about in the rain almost orgasmic with self-indulgent excitement.

"Holy shit, what a day," Robin Judkins, race director, told the press.

Klondyke Corner was being lashed by the storm which was to bring more than 120mm of rain over the 24 hour period.

The sound of incoming helicopters sent a fever of excitement through the media. Red Cross personale were being dispatched up the Mingha to look for competitors in trouble. A hypothermic man was choppered in from Goat Pass and whisked away in an ambulance.

Amid the drama I interviewed Robin Judkins.

Describe to me the day, how it's been for you?

"It's been a marvellous day, absolutely stunning. This is exactly how the event should be — tough and wet, really wet.

There's been a bit of a danger factor.

"Well, yes, it is dangerous when rivers come up into flood.

Have you been worried at all?

"No, the funniest thing is I was never particularly worried about it. I have a lot of faith in the officials that I've got and I've also got a lot of faith in the competitors. They've used their brains today and I'm quite impressed. For the 10th anniversary, it's added a heap of spice. It's just what we needed, a bit of drama."

An eyewitness report from Goat Pass

It was late afternoon when John Woods finally made his run down the Klondyke finish chute. His eyes were bulging and bright from the adrenaline pumping through his veins. Great, the boss had the story — an eye-witness account of the drama on the mountain.

“When we got off our bikes at the Deception footbridge it was just like any other year as far as I was concerned, He said. "The water wasn’t high then, but as we went up the rain was falling in sheets, layers of water and it intensified as we climbed. All the side creeks and little valleys were just thundering with water and by the time we got to the big boulder section people were gathering in groups for support.

“ The first real worry was when we climbed from the bottom of the Deception Valley up to Goat Pass. It’s normally a ten minute climb through a dry rocky river bed. It took an hour for five of us to get up there. As we went up it was just cascading down; steaming, frothing water just bucketing down. It looked fearful, it looked awesome.

“But we made it up and when we got to Goat Pass there was a bit of a panic on. The officials in the hut were on the radios to Judkins. It wasn’t worth sitting around there, the wind was lashing and it was sleeting so I hit the boardwalk with two of the guys out of our group.

"At the bottom of the boardwalk at the head of the Mingha Valley I saw a guy stranded on an island. There were people watching him. We tried bracing six people across the river to get to him but it was just too strong. A helicopter eventually lifted him off and brought him to where Judkins was, where we were all assembled. By then there were about 12 of us and Judkins decided that he would ferry us downstream about 300m to avoid any more river crossings.

“The helicopter then plucked small groups of people from all over this braided headwaters area. There was about 30 of us in two groups and we were instructed by Judkins, and we agreed, to stay together on true right of the Mingha down to the Bealey.

"This meant having to bush-bash our way, stumbling over tree roots and across rock faces that were quite difficult. There was good spirit and people shared food. There were two people in my group who looked hypothermic at that stage. By then everyone had given up their race attitude and people were there for a bush experience, for a survival experience, and it was a lot of fun.

“When we got down to the Bealey we had to get ferried by the chopper once again across to the main highway so that we could run to the finish line. We had been on the run for 7.5 hours but we all felt like winners—there was hand shaking, laughing. It was an accomplishment to get down and out of there. The time was immaterial. The weather reinstated this event as a tough endurance event of the highest order.”

At Klondyke Corner, despite the roar of helicopter engines, I managed to get a few comments from Tim Fahy, the Red Cross Emergency Relief co-ordinator.

What is your group’s role?

"We are all Red Cross emergency relief team members. We are all totally first aid trained and we all have quite a bit of outdoor experience."

What particular situations did you have to deal with?

"Most people were fairly well prepared. There were one or two obviously ill-prepared who did need a little assistance, but by and large it was only to get across the river because it was so high and so swift."

So you had no real medicals?

"One case of hypothermia perhaps, but as soon as he got out he was very quick to recover. So while it looked pretty dramatic, it was under control. It was quite under control, but the potential was quite nasty. If the wind had stayed up and the helicopter had been grounded we would have had to camp people on the other side of the Mingha for the night, which wouldn't have been nice."

That was a contingency?

"Well, it was definitely on there for a while, but luckily Bill Black, a skilled helicopter operator, and others were able to get in and ferry those people out. \"

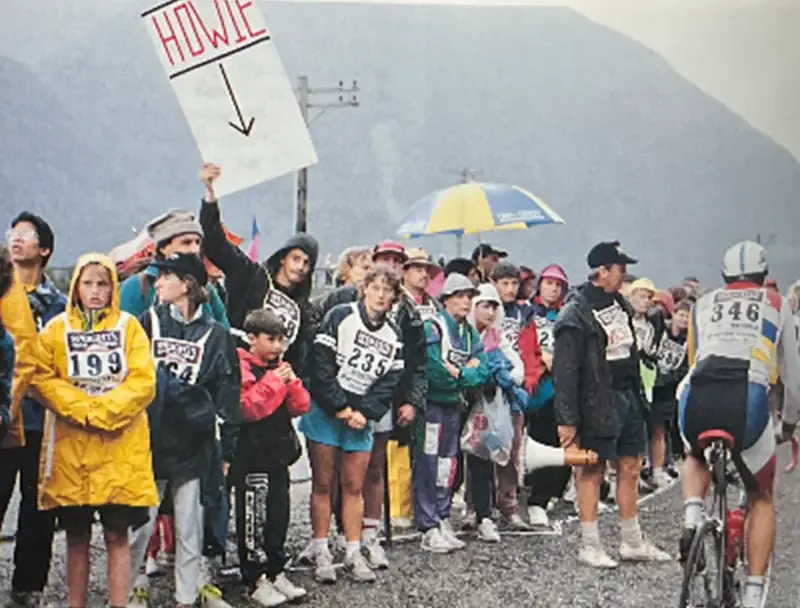

Howie, where are you! Supporters and two-day race team members wait in the rain for the arrival of their cyclists at Deception where they will begin the 26km mountain run over Goat Pass to Klondyke Corner, not knowing that heavy rain is turning the route over the alps into a weather disaster.

The night before the Longest Day

We ordered big steaks steaks with plenty of chips, as many jugs of beer as we could carry and huddled around a table. The Bealey Hotel was full this wet Friday night of the Coast to Coast. The two-day race competitors asleep in their tents and caravans back at Klondyke. We had gone ahead to the Bealey for a "staff meeting".

The accumulation of damp body heat had us stripped down to tee-shirts quickly. It was a time for bravado and camaraderie. We were the jolly fellows of the Adventure team, all wet, laughing and farting across the island in a rented campervan.

It was time-out for a beer and a hot meal but pubs being pubs, McKerrow and I were looking for stories. Eyres was looking for a refill. Woods the competitor, who was not in bed yet, was looking for another plate of chips.

Publican Paddy Freaney joined us. Woods ordered blueberry pie with three helpings of ice-cream. We drew in the company of a foursome at the next table. It was John Jacobs and Ron Collis and their wives. They were the blokes from Amuri BMW who last year put up the car which Gurney won. Big changes within the company meant this year they no longer had any connection with the event, but they couldn't keep away.

"It was something we did that I will always be proud of," said Ron. The wives nodded in agreement. They had come on a sort of nostalgic pilgrimage to watch this year's event. "It gets in your blood this thing, you can't keep away."

"We ran into some other blokes who told us about their mate, a competitor, one of the Kumara locals. Apparently he trained in the bush by chasing down deer and catching them with his bare hands. His name is Clinton Findlay, a gold miner by trade, and he was competing in the two-day race. He was one of the Kumara boys who saw the event pass through town back in 1983 and decided to get involved.

I had a few words with Findlay.

I don't know if they are pulling my leg or not but your mates told me that you often catch deer by running them down?

"Yeah, hinds and that."

They were saying you stick their antlers in the mud and sort of drown them, it makes the meat better.

"No, I just grab them around the head and bring them down. It's quite good really."

What sort of training have you been doing?

"I've mainly been doing mountain running and kayaking and things like that. We go out shooting in the night and just a few weeks ago there we saw this big hind and this little fawn there. So I ran after the fawn and bull-dogged him."

How far did you have to run?

"Say 500 yards. The big sprint, dived on him."

How do you feel about the overall event itself?

"It's a great buzz, just to finish. That's want you go in for."

We slept like logs on our campervan back at Klondyke and the next morning we were up early with the competitors.

The biggest duathlon of them all

They all looked grumpy. Who could blame them on this dismal damp Saturday. The prospect of on a 160km ccycle on this unseasonably cold Canterbury morning was not to be laughed at.

The only person person laughing, giggling again in fact, was the leprechaun who had choppered back to Kumara Beach to send off the Longest Day competitors.

Earlier in the darkness of dawn the word had gone around the tents at Klondyke Corner that the paddle was off and confirmation came at a competitors meeting in the big tent.

"The last check we did on the river was at midnight and the river was still rising," informed timekeeping director Dave Boyd. "At that stage, with the forecast for rain we felt that it would be very unlikely that we would be able to run the river.

"Obviously the biggest problem this morning with the river is the debris and the amount of mud. We obviously could not guarantee safety on the river. There is no way we could put jet boats in there and guarantee to do anything. Last night at last count there were about 14 different braids and it was just getting worse. So the river is closed, there is no paddling. The course that will be run today will basically be a two stage cycle for teams and a one stage cycle for individuals."

At 9.30am the two-dayers set off on in bunches on their bicycles from Klondyke for Sumner Beach in Christchurch, while back at Kumara Beach on the West Coast the big boys and girls of the Longest Day began their race, each chewing over the shock news that this year they would not be paddling kayaks. And that they would be running over Arthurs Pass highway, and not cross-country via the Deception River and the Mingha.

Ahead of them was a run-cycle-run-cycle road race from east to west — the biggest duathlon of them all.

Rockley Montgomery from South Africa set the pace from start to finish.

Rockley Montgomery, the last minute entrant from South Africa, got an early jump on the Kiwi hotshots in the run over the pass and surged eastward relentlessly. Russell Prince, Jeff Mitchell and Steve Gurney have chase but they just couldn't keep up with the tough South African.

In the women's race veteran Kathy Lynch, gritted her teeth as she chased newcomer Claire Parkes across the island. Parkes had taken the lead from Kumara Beach to Klondyke, but Lynch reeled her in and took command in the second cycle leg.

The course changes, with no river paddling, had made it an event of unknown quantities. Anything could happen here.

It is difficult for a journalist who's never done such an event to describe it except with a collection of cliches. How can he understand what makes the seemingly invincible Steve Gurney run out of grunt? Where did Rockley Montgomery get 60 seconds of superior strength. Why was Lynch faster than Parkes when it counted.

It occurred to me that endurance races are won on the day. The same race run a day later could see a totally different result.

Grahame Sisson, who hd pulled out of the two-day event after the kayak section had been cancelled, knew what was happening inside Gurney's head when he jumped into his support van and took over the task of emotionally pushing the flagging champion all the way to Sumner.

As we drove through the outer suburbs, Christchurch seemed like a foreign country after two days in the mountains. The city was going about its normal Saturday business as the cyclists penetrated its urban environs.

We chased Rockley, Mitchell, Gurney and Prince through the city streets. The leaders were only minutes apart but it was obvious the placings would not alter.

The mid-field two-dayers were still fulfilling their final obligations by taking a can of Speight's beer from the hand of Judkins as the one-day throuighbreds galloped to the finish.

The crowd at Sumner Beach was on its feet to cheer Montgomery up the final metres of the finish chute to record a total time of 8:37:30. Jeff Mitchell, the 29-year-old tria-thlete from Nelson, proved his pedigree is improving by finishing just 66 seconds behind the winner. Gurney relegated himself to the rank of mere mortal by finishing third a further 30 seconds later. Inaugural Longest Day winner Russell Prince was two minutes behind Gurney.

They grouped on the dais in front of the Toyota SR5 Fourrunner, the prize for breaking the record which had been made redundant by the weather. The car would wait for next year and Gurney's 1991 best-time of 10:56:14 would remain the target to beat.

The top four men competitors in the Longest Day race — Jeff Mitchell, Russell Prince, Rockley Mongomerie and Steve Gurney.

The next bit of excitement was the arrival of women's winner Kathy Lynch — 14th overall — in a time of 9:29:36 .

Claire Parkes came in second a half hour later.

The rest of the field came in over the next several hours—men, women and veterans in all the various categories—the people you generally only read about in the results columns. It looked like a opportune time to interview the front-runners so I started with Rockley Montgomery. a South African ultra-distance tri-champion, age 33.

How did it go for you?

"I must have hit the wall about five times, but not badly. I was keeping myself basically within my limits and just watching the guys behind and making sure no one closed up. When the boys got closer than 30 seconds I started picking up the pace a bit."

Do you feel disappointed that you didn't get to do the proper course?

"Very disappointed. I mean, I came half way around the world to do the original Coast to Coast. It might not have turned out better for me. I won today, I might not have won tomorrow."

You're going to get some good prizes, but not the car.

"Yeah well, that's life, you can't win them all.

Are you going to come back? You said you'd like to.

"Yeah, very much so, except I reckon next time I'll be a totally different person because next time I will know what I'm training for what to expect and I'll do the training for it."

Mentor Grahame Sisson jumped in to help Steve Gurney's support crew urge their struggling competitor on and was at there for his friend at the finish.

Woman's Longest Day winner Kathy Lynch was disappointed about the change of course but said "at least we had a race. You can't change the weather can you. Anyway, the worse the weather gets, the better I go."

Main rival Claire Parkes held the lead over Lynch up to the second cycle stage but the champion said she always had Parkes in her sights.

"We went over the top together, more or less, and then one of my shoe laces came undone so I stopped to do that up and then I wanted to go to the loo. She got out of sight then so I just plodded along at my pace anyway because I knew she wasn't going to take too much out of me on the down-hill."

Commenting on how she caught Parkes in the final cycle leg she said: "If you're in a race and there is someone out front you go get him straight away, you don't go chase him 50km up the road. You rip into it so then you know where you're at—you don't hang back if you're out to win."

Lynch had stern words for her Kiwi male contemporaries who were beaten by the South African unknown.

"Right at the start of the race on the first cycle leg Gurney was sitting in a pack not wanting to do any work. As normal no one wanted to do any work. The South African just took off up the road and no one even chased him. I thought 'there goes your race' and no one did anything.

"Rockley did a good time on the hill and they just let him literally ride away on the first stage and that was it. He took two minutes out of them and he won the race by two minutes."

Lynch vowed to return in 1993. "For sure, I want to come back and do the real course. I really trained hard for that run and I got my canoeing going really well and I was looking forward to doing a brilliant time on the run and I never got a chance to do that—so I've got to come back next year."

I also spoke to the women's runner-up Claire Parkes who seemed in shock from the blitzing she received in the final cyle leg from Lynch.

All that training for the mountain run and the river—are you coming back next year?

"No, I don't want to be disappointed again."

In the run, you were in the lead ahead of Kathy.

"I was, but I didn't do as good as I had hoped.

You were first out on the final cycle?

"I was first on to it but Kathy just blitzed me."

I then sidled up to Steve Gurney who was also having a moment of reflection.

What happened?

"There was a lot of strain on the bike, 220km is a bit far for me. I've been training for 70km. The problem was I bombed. I hit the wall at about Mt. White bridge. Psychologically that's all I was expecting to cycle, and then 20 minutes after that I bombed real bad and took two hours to get out of that.'

You were a bit dejected when you hit the top of the pass, too, they say.

"I actually came to a stop there. Something was drastically wrong. It was good that Grahame (Sisson) came along. He jumped in the van with my crew and gave me a good kick up the butt. He made me eat some more and put some more clothing on. He psyched me into it."

You gained on Montgomery but he was just too far ahead.

"The thing is I was one minute behind him at Mt. White bridge. I was following him in, I was in second place and I thought, 'great I've got him' and then I just blew apart which was really annoying."

Was that when Mitchell got past you?

"No, he got past about 30 minutes later. I'd been going quite easy, I wasn't going hard so it surprised me when I bombed. I thought I'll pull him in by the time we get to Christchurch no problem. I didn't want to go too hard too early then blow it. I'm really disappointed. I just guess you get these days like in training."

Grahame Sisson said he didn't think you were getting the right support. You had the wrong wheels on your bike.

"It was my fault again. I'm not blaming anyone, it's all my fault. I told my crew to put on the wheels off my blue bike, but I've got two blue bikes. I should have specified which blue bike. They ended up putting my old training wheels on."

That would have been unnerving wouldn't it?

"Yeah, I don't know. I don't think that was to blame — it was just that I bombed and that extra run, I just didn't eat the right sorts of food, I think. I learned a lot out of this race in that you have to re-member you can't always be on top. You'll get these times when you get knocked down. You've got to take it in your stride. Another thing I realised in this race is that my sponsors The Design Team have got a good logo, 'words are words, talk is talk, excuses are excuses, but performance is reality'. That's true. I just didn't perform yesterday. The other guys did and I got beaten."

The aftermath

Judkins and his team stayed at the beach to greet the late finishers. We sculled a few cans of Speight's then bolted. We picked up John Sweeney from Twizel walking along the road. He jumped in the campervan and we went to the nearest pub.

There was a good crowd of Coast to Coasters and an electronic game going on called the Speight's Post to Post. Woods soon had a team organised and a challenge entered.

It was very late, around 2am on Sunday morning, when we knocked on the door of a certain motel room. We knew where to get a beer this hour of the night. The big fellah, Rod's father Kevin, came to the door in his singlet. We were welcomed in and one by one they crawled out of their beds.

Kevin ripped a tray of Tuis out of the fridge. For these were the boys from Wairoa who come south each year with their van van loaded with huge amounts of their local North Island brew to support their boy Rod Kirwan.

Rod — who had only hours before finished the Longest Day — woke up and joined the party. It was time for some really tall stories.

With the sun not far from rising on a brand new day, McKerrow came up with the best one.

"Did you hear about the bloke who ran through the finish line with a peanut slab in his pocket. They zapped him with the barcode gun and he recorded a best ever time of $1.20!"

One of the great challenges remaining in the profession of journalism is the never-ending quest for a free lunch.

The next morning we rolled out of the campervan wth this in mind and turned up for the prize-giving function at the Christchurch Town Hall where, between plates of baked ham and bowls of pavlova, there were several last minute interviews to be made.

There was John Gillies, the oldest competitor at 71 and a diabetic, who had a message about never giving up.

"There's an awful lot of misconceptions about diabetics. They shouldn't be coddled — kick them in the arse and get them cranking because there's no doubt about , I am fitter and have less trouble because of the exercise."

Asked about the run over Goat Pass in the storm he said: "I've been up in the hills before and you don't give you give up,

There was Joe Sherriff, the first person across the line in the first event 10 years ago. He came back to have another go this year with the same bicycle and the same pair of cycling shoes he wore to win race in 1982.

And Joanna Kane, the last person to finish the event this year—she kept Judkins waiting until 10pm. She may have been the slowest competitor, but she epitomised the true spirit of this race. She wanted to give up, but didn't

The 37-year-old swimming instructor and mother-of-two admitted to being in Gagaland'for the last 70km of the bike ride.

"All I wanted to do was get off the bike but I knew I was going to be the one to wipe the smile off Robin Judkins' face by making him wait for me. It didn't worry me coming last—it was a test of my own mental and physical strength to get through it."

The South Island receded into the distance as we flew out of Christchurch and put the Coast to Coast behind us for another year. The laughing leprechaun was on another aircraft somewhere, heading to the United States to spend his gold.