The Tsunami

On a Sunday morning in February of 2010 an earthquake half the globe away sparked a tsunami emergency on the East Coast of New Zealand, sparking memories of more violent events 60 years earlier.

The centre of the bay at Wainui crept quietly in and out several times during the day of the Chilean earthquake tsunami emergency on February 8, 2010. Despite the civil defence alert and warnings to keep off the beach, Wainui remained a popular venue for surfers and recreational walkers throughout the day.

Sunday morning, February 8, 2010, and a stunning day dawned with the sunrise at Wainui Beach noreth of Gisborne. Then rudely, the promise of a last tribute to a long hot summer was shattered by fast-spreading news that a potentially devastating tidal wave was heading our way. The magnitude and the source of the earthquake that spawned the threat, 8.8 magnitude and off the coast of Chile, stacked up to create a nationwide tsunami alert of life-threatening probability.

The first fears were that the tsunami would hit our local beaches at 7.59am. However the first surge arrived at 8.20am and measured just 40 centimetres. It was hardly noticeable. Earlier reports of less-than-life-threatening surges from the Chathams had allayed fears that Gisborne was to be inundated.

The day turned into a coastwatcher’s field day with dozens of quietly dramatic ebbs and surges to be observed as the disturbed waters of the Pacific oscillated around our shores for several hours, like water in a bath tub.

The most dramatic scenes were at beaches where the underlying reefs were alternately covered and uncovered as if the tide was changingfrom high to low every 10 to 15 minutes.

At times, the centre of Wainui bay emptied out dramatically to reveal seldom visible sandbars. Winifred Street resident Linda Coulston watched the sea level in the bay rise and fall at least six times. She contacted the New Zealand Herald and as a result a photo she took appeared on the front page of the national paper the next morning.

At the Pines area and north of the surf club, large areas of usually submerged jagged reef became exposed during the ebbs and was covered again by the surges. Wainui lifeguard Jeremy Lockwood said while the sea appeared flat, there were strong currents under the surface associated with the tsunami.

Lifeguards were given the onerous task of asking people to move off the beach for their own safety. However, even at the height of the warnings before 8.00am, and during the entire day as the tsunami warnings remained in place, Wainui Beach on such a nice day was irresistible to many. Joggers jogged, walkers walked and surfers surfed throughout the civil defence alert. At Stock Route, at the southern end of the beach, a Gisborne Boardriders Club veterans’ surfing contest continued despite the alert.

Linda Coulston said right from 7.30am, when the tsunami alert was at its peak, she observed numerous groups of people, including families with children, watching the sea from the sand dunes along Moana Road. “I couldn’t believe it, at that stage no one knew what was coming.”

The photos above were taken just minutes apart. The sea ebbed and surged at 10 minute intervals exposing seldom-viewed reefs at the central section of Wainui beach.

Local surfing identity Dave Timbs observed the surf from his home overlooking Stock Route and was one of those who eventually went out surfing.

“I was woken by an overseas call that there had been a big earthquake in Chile and there was a chance of a tsunami here. I know from swell forecasts that the only tsunami we might get at the southern end of Wainui Beach would be from an underwater landslide just off the coast, and then we would have very little warning, or from an earthquake in Chile which could produce a serious tsunami.

“So at 1.30am I watched BBC News and checked out the internet. It looked like we had until at least 7am before the Chatham Islands would be affected, so I set my alarm for 7am and went back to sleep. When I awoke the Civil Defence website said the first tsunami pulse should arrive at 8.30am and that the Chathams had earlier recorded a 0.4m pulse. We were off the hook,” Dave decided, “and not in for too much.”

So after 8.30am, all the local surfers and the Gisborne Surfriders Club contest competitors hit the water and surfed until the onshore winds picked up later in the day.

“From the accounts of surfers I’ve met who were out surfing off an island in Indonesia when a major tsunami came through, it seems if you are far enough off the shore and the surge is a relatively small one, then it is quite safe to be surfing in such a situation,” Dave said.

The general feeling amongst the surfing fraternity was that they had acted responsibly. They had listened to the warnings, monitored the arrival and size of the surge at the Chathams, watched the arrival and size of the surges at Wainui and then decided there was little to no danger of a rogue surge of life-threatening size hitting the local beach.

Surfers and residents were also aware that Wainui is often pounded by waves higher than three metres. Beachfront houses along Moana and Wairere Roads are built on sites that are approximately 10 to 13 metres above mean sea level – about the height of a four storey building. It would require a wave of over 10 metres to reach front door steps.

While fascinating because of the unusual nature of the surges, the actual effect of the tsunami here was minimal. This time.

Okitu storekeepers Gary and Maryanne Quinn and family were amongst those who decided it was prudent to get to higher ground, heading for the safety of Winifred Street, at least until the threat had passed at 9.00am. Linda Coulston said when she was awoken by news of the impending tsunami around 7.30am, there were already at least 100 cars parked along the heights overlooking Wainui from Winifred Street.

While the Okitu Store was late to open that morning, the Wainui Store was open as usual, staff reporting a busier than morning with regulars and sightseers from town queueing for coffee.

This writer, along with Tessa and Sean McCormick, Debbie Wooster and Chrisse Robertson were camping in tents at Kaiaua Beach, north of Tolaga Bay, on the Sunday morning. We were woken before dawn by a Civil Defence warden and urged to make a hurried evacuation

“The man told us the tsunami was going to hit the coast at 7.30am. It wasn’t till we were able to get radio reception up on the highway we realised that there had been no real need to panic but for a while we were fizzing as we rushed to dismantle the beachside camp site.”

Later the group witnessed several dramatic surges as Turihaua Bay drained out to expose large areas of reef for ten minutes or more – then be covered again as a sheet of water quietly surged back to totally submerge the reef, with 0.5 metre “mini-tsunamis” rolling up the beach with each surge. This cycle repeated itself for several hours. At least one diver could be seen taking advantage of the “low tides” way out on Pouawa reef.

In the wake of the alert, GeoNet reported that tsunami surges hit Owenga Wharf on the Chatham Islands east coast at 7.25am and again at 8.10am.

At Gisborne, the first surge was reported in the harbour at 8.20am. Geonet said waves of nearly two metres (peak to trough) were observed on Chatham Island and at Gisborne. The unusual sea level activity continued at all recording sites for at least 24 hours after the first arrivals.

The magnitude 8.8 earthquake that occurred off the coast of Chile resulted from the oceanic Nazca plate being thrust under the South American plate. The subsidence generated a tsunami which propagated west-north-westward across the Pacific Ocean. The largest waves were not expected to hit New Zealand. However, GeoNet says numerical simulations of the likely effects of the tsunami on New Zealand predicted measurable waves with amplitudes of between 0.2 and 1 metre along much of the eastern coast.

Historical accounts suggested that the largest waves would arrive between 6 and 12 hours after the initial arrivals – this was most evident at Gisborne. The secondary larger waves were due to reflections of the tsunami from other parts of the Pacific arriving in New Zealand later than the direct waves and adding to the activity already under way.

1947 tidal wave showed what could happen again

The tsunami of 26 March, 1947, flooded the Tatapouri Hotel, north of Gisborne, up to the window sills. Minutes later the receding tide sucked small outbuildings into to sea.

At 8.32am on 26 March, 1947, a seemingly minor earthquake jolted the Gisborne area, generating a tsunami that 30 minutes later swamped the coast from Muriwai to Tolaga Bay.

Four people in the hotel near Tatapouri Point, north of Gisborne, spotted an ominous wave offshore and dashed up a nearby hill. Two successive waves drove through the hotel’s ground floor, filling it to the window sills. Many minutes later the receding water sucked small outbuildings out to sea.

At Turihaua a large wave bore down on a cottage. Two men outside were swept inland and dumped on the coast road. Two women and a man were trapped in the kitchen of the cottage, which filled to head height with water. Battered by debris-laden water rushing back to the sea, the cottage crumbled. Only the kitchen was left standing.

At Pouawa Beach, the Pouawa River bridge was carried 800 metres upstream. At Te Mahanga Beach the tsunami shifted a house off its piles, and at Murphy’s Beach six hectares of pumpkins disappeared out to sea.

Less than two months later, on 17 May 1947, another offshore earthquake generated a tsunami that hit the coast between Gisborne and Tolaga Bay. At its maximum, north of Gisborne, this wave was about six metres high.

No one died in either of the 1947 tsunamis, but the toll could have been high had they struck during summer holidays, when the beaches were crowded.

“It is a day I will never forget,” said eye-witness June Young (née McLauchlan). “At about 9.20am, I was about to go out through the front door of the Tatapouri Hotel, where I lived with my parents, the managers, when I noticed that the sea was lapping on our front lawn. At the time there were only my parents, Hony and Bill McLauchlan, and me at the hotel. I called out to my father to look at the sea. He took one look and called out to mum and me to run for our lives up the hill behind the hotel.

“We were able to stop any travellers before they drove down the hill. What an awesome sight to be able to stand well out of danger and watch first one, then another tsunami race across the ocean and smash onto the land. The first wave took everything other than the hotel out to sea with its backwash. We could see a shed that was full of furniture, a small dinghy, a two-roomed cottage, plus a variety of other objects. Then came the second wave, which dumped everything back almost where it came from; but this time everything was smashed. Seaweed was left hanging in the telephone and power lines.

“The waves pushed in a half-wall enclosing the verandah, saving a lot of damage to the hotel. I had left the front door open, which saved the door from breaking, but let in a lot of water, sand and little hoppy things. My sister Margaret had, as usual, gone to the Pouawa School in the service car. They had just gone over the Pouawa bridge when water came up the river and washed the bridge away. For some time afterwards the school children had to be taken across the river in row boats until a Bailey bridge was built.

“No lives were lost, but there were many stories from people who might normally have been in the path of the waves, but for one reason or another were not there at the time.”

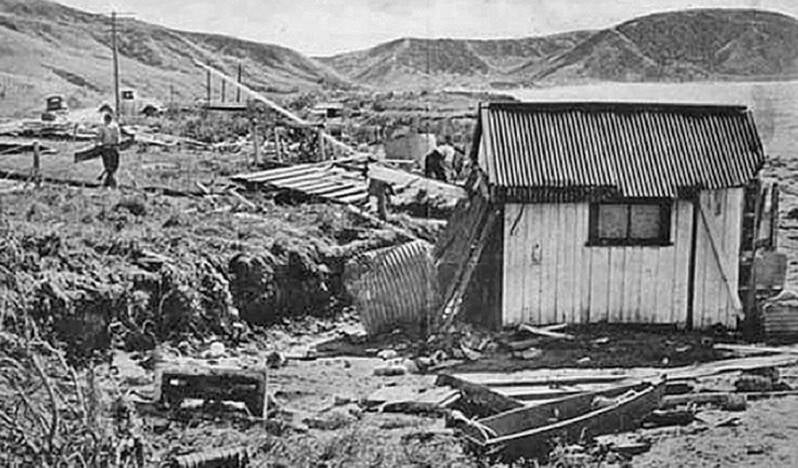

A locally generated tsunami near Gisborne on 26 March 1947 caused widespread damage along the coast. This is all that remained of a four-roomed house at Turihaua Point that filled head-high with water. Seaweed was left hanging in the powerlines in the background.

The bridge across the river at Pouawa was washed a kilometre upstream.