The Return of the Longboard

Riding a wave of surfing nostalgia

Written for Southren Skies magazine in 1996

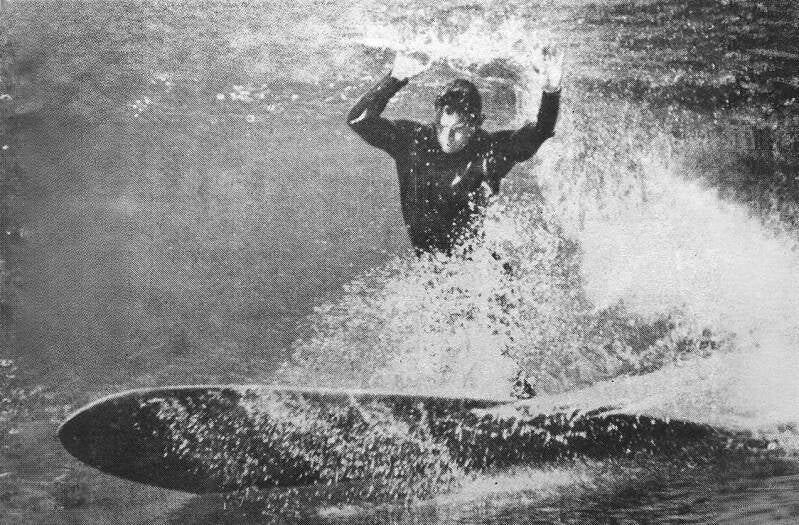

Owen 'Smiley Boy' Williams of Wainui Beach, Gisborne, was one of the earliest surfers to think outside the modern square in the mid-1980s by embracing the equipment (he made his own boards) and moves of a former era.

There's a grassroots revolution sweeping the sport of surfing. Some call it a renaissance, others a regression. It's the return of longboarding—a style and attitude of surfing that was around when the Beach Boys were in vogue. This news may seem trivial to the non-surfer, but put in rugby terms it's as radical as reverting to the rules, style and equipment of the game as it was played in the 1950s.

In the United States nearly half of new surfboard sales are now longboards (over eight-feet in length), and a similar pattern is emerging in New Zealand. Specialist longboarding magazines are thriving. A richly sponsored worldwide longboard competition circuit has evolved. The surf-related clothing and accessory manufacturing industry has quickly geared up to satisfy a multimillion dollar demand for longboard-genre clothing and paraphernalia, cashing in on a wave of nostalgia sweeping surfing culture.

On any beach in the world today there is conflict out in the surf. Not only are surfers competing for the best and biggest waves, they are head-to-head in a conflict of style and perception.

Shortboard surfing is the leading edge of the sport's dynamic progression. Surfers who master these highly manoeuvrable dart-shaped wafers of polystyrene foam and resin earn godlike status and professional incomes. In the politics of surfing the champions and the bureaucrats of the shortboarding establishment hold the power.

Though shortboards have been around since the mid-sixties, there have always been diehard longboarders who chose not to follow the new shapes and designs. Shortboarders regarded them as eccentrics and old-timers happy to dream about the good old days and rave about the way things were. Their nostalgic passion existed off to the side of surfing's mainstream. Now they're on the rebound, and they're causing—as well as catching—a few waves.

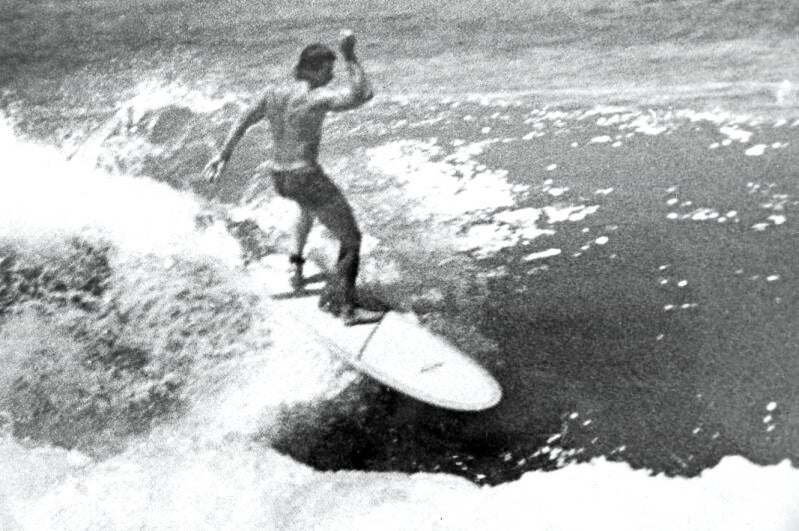

James Tanner of Wainui Beach, Gisborne, was just a teenager when he followed the path forged by his father Sam and a group of like-minded longboarding stalwarts and in doing so took the sport to a new level of style and athleticism.

Kelly Ryan was another of the younger new age longboarders from Gisborne who took his skills to the national competitive arena and longboarding into the mainstream after the turn of the millenium.

Surfing is firstly a sport, secondly a culture, thirdly a relgion. From an evolutionary perspective it can be viewed as a unique diversion in the development of the human species. In his prophetic novel Future Shock, Alvin Toffler wrote that the surfing lifestyle represented a wave of the future, and that the surfing subculture demonstrated that "a leisure time commitment can serve as the basis for an entire lifestyle. The surfing subcult is a signpost pointing towards the future."

The history of surfing has been well documented in recent years, with several books which have become references, if not Bibles, for most longboarders. Surfing's Genesis is set in the Garden of Eden of the Hawaiian islands. Legend and reality have blurred in the oral retelling of its ancient origins which date back to the 15th century at least. Captain Cook was the first European to observe surfing on his visit to Hawaii in 1770.

In later years, surfing declined as missionaries tried to alter traditional Hawaiian culture to fit Christian ideals. Surfing on solid wooden boards was not to re-emerge until the early 20th century with the advent of Hawaiian lifeguards who were employed to protect the growing numbers of tourists flocking to Waikiki. It was in the pre-World War I period that the legendary Duke Kahanamoko, the most famous name in the history of surfing, was in his heyday. Duke, an Olympic swimming champion, introduced surfing to the mainland United States, and in 1915 he was invited to Australia to give an exhibition of surfing at Sydney's Freshwater Beach.

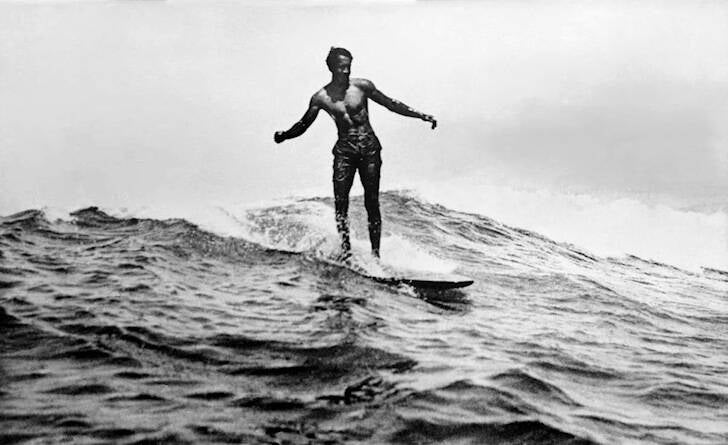

One of the earliest photographs of Duke Kahanamoko surfing Waikiki in the early 20th century.

Ian Proctor was one of the leaders of the longboard renaissance who embraced the spirit of the Hawaiians in his unique and demonstrative style of riding the waves around Gisborne.

After the First World War, surfing took on a new direction through the genius of Tom Blake, a nomadic adventurer who fell in love with surfing in Hawaii and experimented with hollowing out the, until then, solid redwood boards. With the Duke and Blake spreading the word, surfing boomed in California and Hawaii between the wars, and the surfing life-style started to grow.

It wasn't until around 1956 that polystyrene foam began to be used, and Malibu Beach in southern California became the testing ground for the finer-tuned surfboard shapes which the light new product afforded. As the sixties rolled along, surfing was hijacked by Hollywood. While real surfers laughed at the big screen's geeky attempts to cash in on the beachboy image, the general public was brainwashed with a wacky vision of surfing that in many places still endures to this day. This was the classic period that most of today's nostalgia is focused upon. It was also about the time that surfing arrived in New Zealand, bringing with it the southern California subculture.

During the early sixties surfboards were still mostly over nine feet in length. They were heavy and hard to turn, and riding them well required strength, well-honed skills and a certain natural ability. The masters of this period are still heroes to many longboarders today. Names like Mickey Dora, Phil Edwards, Greg Noll and David Nuuheiwa are as holy to longboarders as the saints are to Catholics. The styles and manoeuvres they perfected—nose riding, hanging five and ten, walking-the-board, soul-arches, drop-knee cutbacks—were duplicated the world over.

This era ended abruptly in 1966 when Australian Nat Young rode what was then considered a shortboard to win the world surfing title. According to surf historian Leonard Leuras in Surfing – The Ultimate Pleasure: "The usually arrogant Americans were rendered speechless. The so-called 'Animal' from New South Wales showed up in San Diego and proceeded to literally blow away his American competitors in their own back yard."

Young's coup marked the dawning of an era of Australian dominance of competitive surfing and the crumbling of surfing's Californian mystique. It also marked the beginning of the shortboard era, which has continued its frenzied and dominating progress until today.

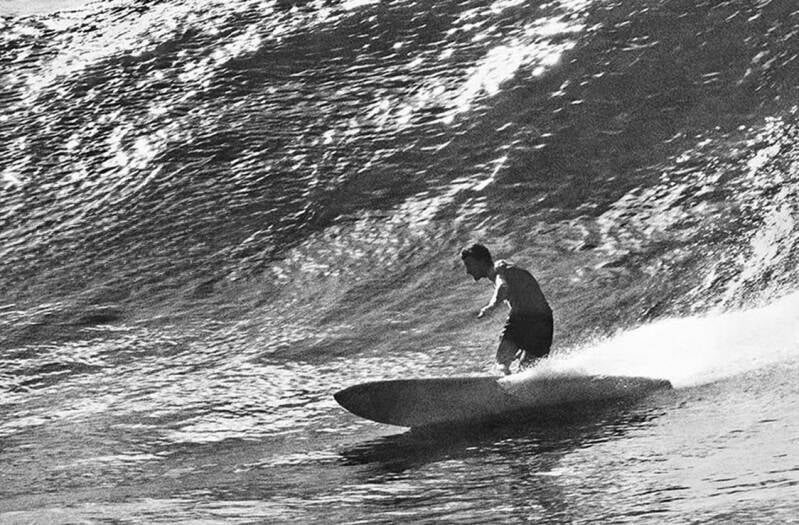

The turning point. Nat Young heralded in the shortboard era after winning the World Surfing Championship in 1966.

Legends from surfing's earlier days, Mike Holmquist, Greg 'Red' Robertson, Benny Hutchings and Larry Foster have been drawn in to latter-day competitive longboard surfing events.

Though longboarding has languished as an option up until now, one factor in its favour can not be denied – a longboard is more buoyant and easier to paddle, and can usually catch a wave earlier than a shortboard.

In the surfing religion there is only One Commandment: "Thou shalt not drop in." Translated, this means that if someone is already up and surfing on a wave you do not take off in front of him. So, technically and legally, longboarders rule the waves. This was fine while numbers were minimal, but in recent years, with interest in longboarding increasing, this once tolerated eccentricity has become a threat to the dominance and control of the sport by the shortboarders.

While there is conflict, it is one in which the battle lines are hazy. The main reason is that it is difficult to spot the enemy, with many surfers paying allegiance to both camps. Today's surfer usually has both styles in his quiver of boards, and many of the top exponents of the art are young surfers proficient at both types of riding.

Still, if you're at the beach huddled around a driftwood fire at the end of a perfect day, you will hear rumblings of discontent from surfing's shortboard hardcore. Many are resentful of the advantage the bigger boards have in the water, and openly accuse longboarders of getting greedy, catching wave after wave and not obeying surfing's unwritten rule of waiting your turn.

New Zealand Surfing magazine editor Chris Berge agrees: "Some of the older boys, who maybe haven't caught a decent wave in 10 years, are probably getting a bit over-enthusiastic. I can appreciate where they're coming from though."

Bob Davies, 53, New Zealand's living legend of 1960s surfing, board manufac-urer and former surfing champion, is pragmatic. "A lot of surfers have got older," he says. "It's a pretty natural thing to go back on to a longboard. You can get out, paddle, catch waves and enjoy surfing that you couldn't on a little wafer-thin blade."

Davies reckons the longboarder has to be fair about the advantage he has in the water. "There's got to be a bit of give and take in the sport on both sides," he says. "Four or five years ago, you were a kook if you rode a longboard, but that's changed. I think with the modern equipment, longboarding is not a passing trend but part of what is going on. Some young kids are surfing longboards from scratch these days. Now you just go out and surf on whatever you're comfortable with."

Berge agrees: "We're all getting older and, hey, if it means I have to jump on a longboard to keep surfing then I will. It's just reinjecting what everybody started surfing for in the first place—they're re-discovering the fun aspect all over again. That's the important thing."

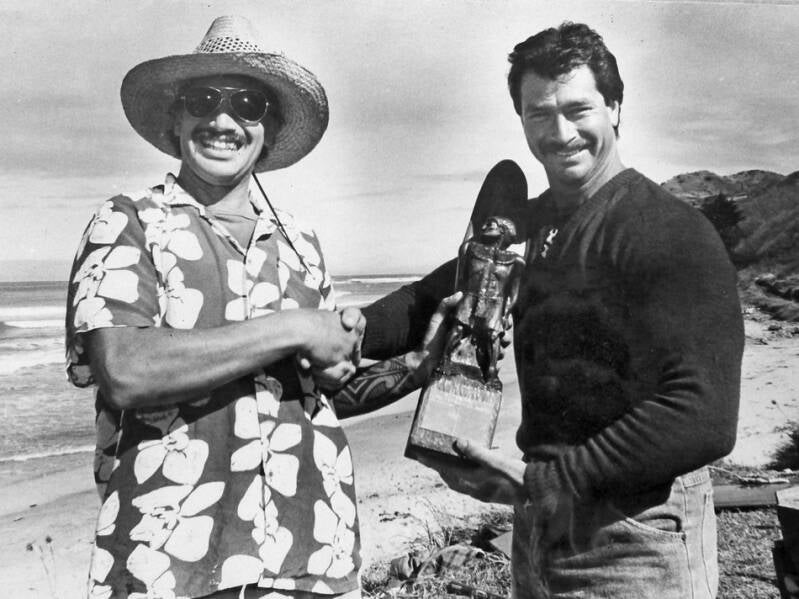

Darryl Williams took part in the longboard renaissance in the 1980s, showing both skill and courage by riding the waves around Gisborne after losing a leg in a motorcycle accident.

Ian Proctor presents Darryl Williams with his trophy for winning an early longboard event held by the Moananui Longboard Surfriders of Gisborne.

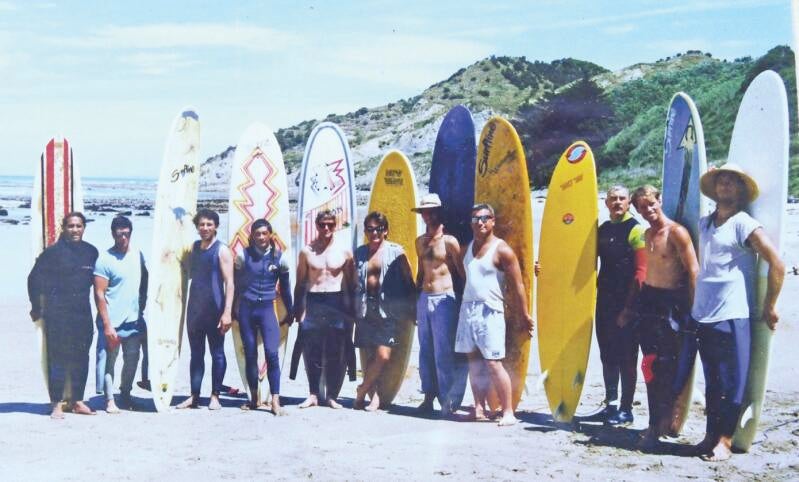

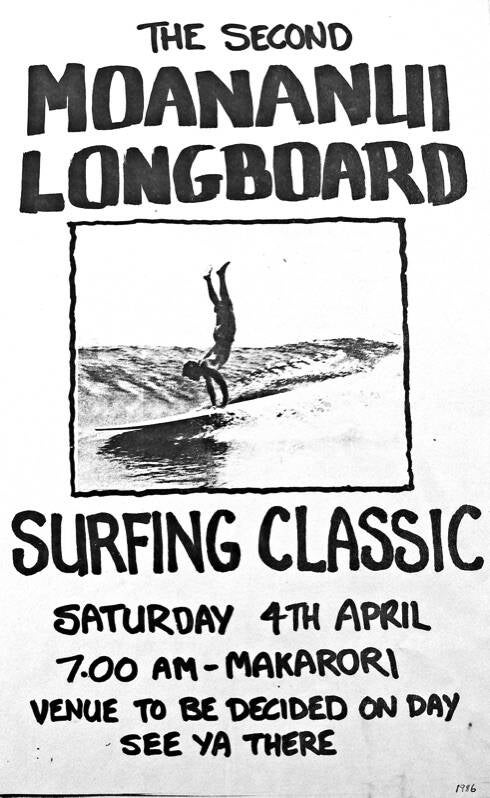

The Moananui Longboard Surfriders Club of Gisborne was one of the first groups to embrace the longboard renaissance in the 1980s. The club was the inspiration behind the annual Makorori First Light Surfing Classic which has been held annually for the last 30 years.

A Moananui Longboarders Christmas party gathering in Gisborne in 2009. The club still gets together for social events several times a year.

Above: A series of posters creted to prmote longboard suefing events in Gisborne since the 1980s.