The Place To Be Beside The Sea

A history of the Chalet Rendezvous

Written for Beachlife magazine in 2009

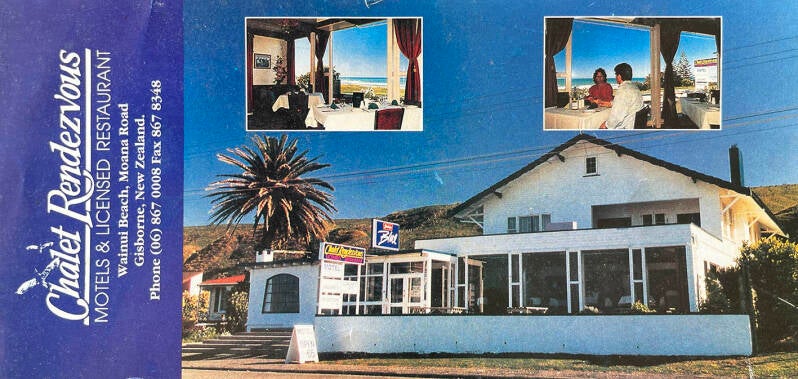

There’s one address at Wainui Beach that is firmly entrenched in the folklore of this community. The Chalet Rendezvous, the faux-Swiss alpine restaurant at 62 Moana Road, Okitu, contains a potpourri of memories for the many people who owned it, worked in the kitchen, bar or dining room or were regular customers in its varied manifestations as a restaurant, guest house and local watering-hole since the mid-1950s. Initially the high-rolling dream of an eccentric European restaurateur it became famous nationally for its unique location, exceptional food and service and for its ground-breaking of New Zealand’s once restrictive liquor licensing laws. So let’s go on a ride back in time to see what we can find out about this fabled, often foibled, local establishment and the people whose lives it touched.

Note: Much of this "history of the Chalet Rendezvous" must be read between the lines as things were not always wine and crayfish cocktails. Thanks to all who were willing to trust the writer with very personal details of their lives to make this story possible. I have taken out some of the original material used in the printed issue of Beachlife magazine. Some of the people involved, who gave full details of their experiences, took exception once they saw their memories in print and asked for them to be removed.

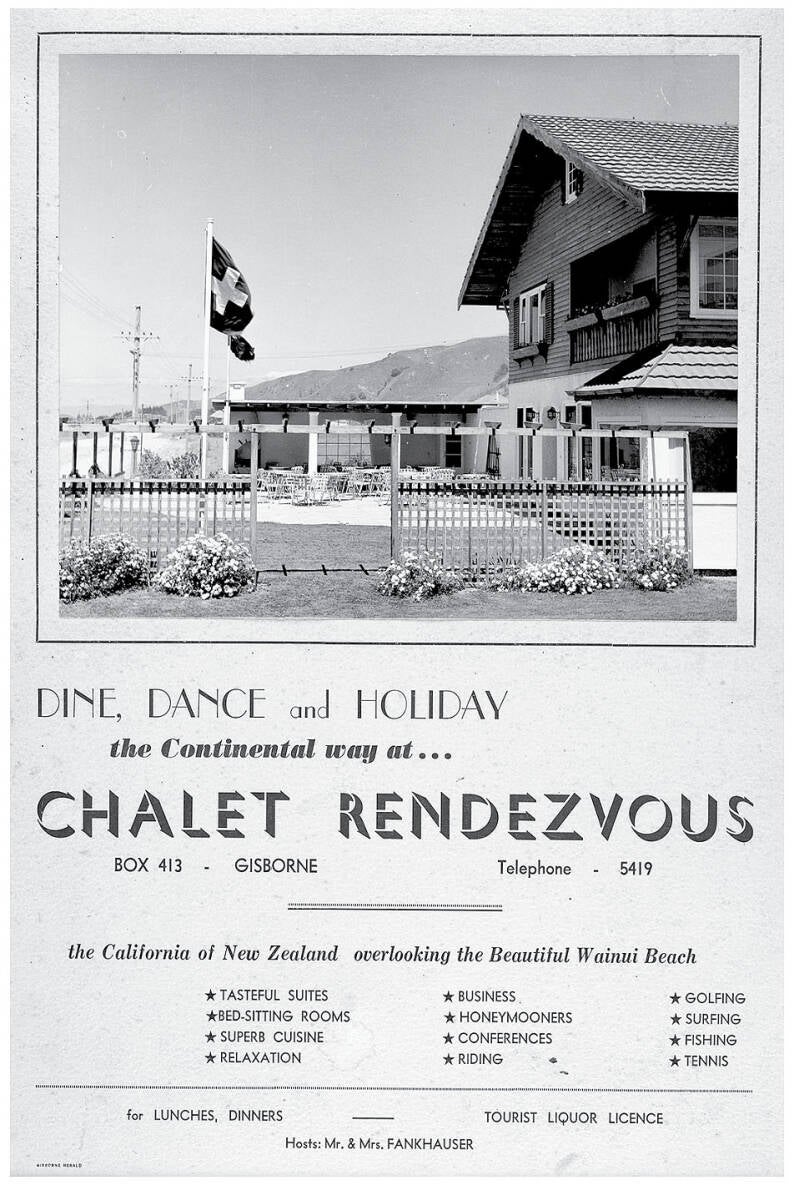

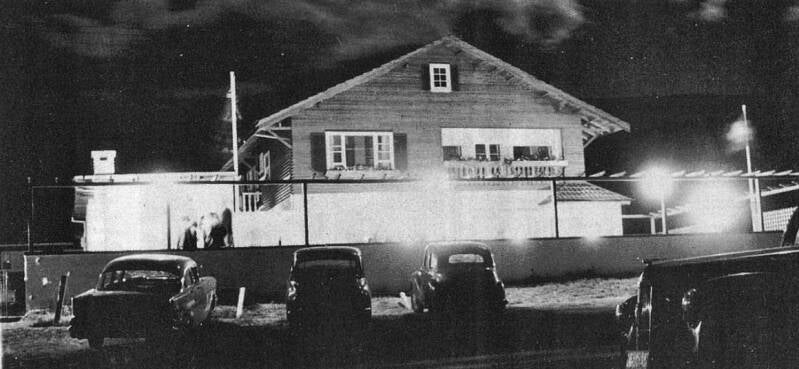

The original Chalet Rendezvous complex in the late 1950s surrounded by empty lots overlooking the beach, with the newly “Tourist Flats” behind.

CHAPTER ONE: The Swiss Connection

We don’t know a lot about Charles and Hedy Fankhauser. We do know they came to New Zealand from Switzerland in the early 1950s. And we do know they travelled and discovered Wainui Beach and saw the potential here to realise a dream they carried from the other side of the world – a novel concept to construct a grand, Swiss-alpine chalet to house a fine-dining restaurant overlooking the ocean.

Background information about the Fankhausers before their arrival in Gisborne is minimal. Although a name of German-Austrian origin, the Fankhauser’s had earlier immigrated to New Zealand from Switzerland where Charles had previously worked as a chef, specialising as a patissier with a particular talent for creating sweet desserts. Fankhauser described himself as an “experienced restaurateur holding a diploma from the Swiss Government in recognition of his qualifications in this field.”

We can only imagine what made them decide on Gisborne, or precisely Wainui Beach, for such a novel and somewhat eccentric business enterprise. However, this was 1955 and Gisborne was looking forward to a progressive and bright future.

The New Zealand economy was in an upswing. Gisborne was a busy provincial town and people had money to spend on nice things, like dining out. In the 1950s New Zealander diners had a limited choice both of venue and menu. Dining rooms of hotels served a narrow fare of grilled or roasted meats with boiled vegetables. Places like the Lyric Cafe in Gisborne, where the hot plate and the deep-fryer combined to provide fish, steak, sausage and chips dinners. These fish and chip restaurants were the forerunners of the “gourmet” restaurants that were emerging in the big cities as a more sophisticated culture of food, cooking and “bistro” dining developed in the late 1950s. New Zealanders returning from experiences abroad and an influx of European and Middle Eastern immigrants eventually widened culinary expectations here.

At the time the Chalet Rendezvous was being built six o’clock closing was still the rule and serving alcohol in places other than public bars was subject to stringent regulation. At the same time tourism was just starting to be recognised as an important national industry.

The Fankhausers must have seen a bright future for themselves at Wainui Beach and confidently set about realising their dream of creating a sophisticated, “continental” dining establishment. On the 19th of September, 1955, they signed a purchase agreement and paid Winifred Lysnar £1150 for an isolated block of land along Moana Road. The area had not yet been developed with empty paddocks all the way to Makorori hill.

Charles and Hedy Fankhauser came to New Zealand from Switzerland in the early 1950s and discovered Wainui Beach where they saw the potential to realise a dream to construct a grand, Swiss-alpine chalet-style building to house a fine-dining restaurant overlooking the ocean.

Plans were drawn up and local builders Wagstaff and Porter began work on the construction of the curious building which looked like a prop from the “Sound of Music”. When the roof went on in April of 1957 Charles Fankhauser had a decorated pine tree roped to the highest point of the structure. “An old Swiss custom”, he told those who came out to view the building’s progress. The Gisborne Photo News reported: “The building is part of the Fankhauser’s plans to provide holiday-makers with first class accommodation and dining facilities at Wainui Beach, which he considers ranks easily with the most famous of Mediterranean beaches.”

A Gisborne Herald report from 1957 stated: “In planning the main building the proprietors chose a site easily adaptable to their main purpose, the conduct of a tourist house with all the elements of a seaside resort. Almost every room has an attractive ocean view and from the principal public rooms the panorama seen from the large windows is magnificent.”

The article continued: “The kitchen is indeed the heart of the enterprise for it is here the proprietor Mr Fankhauser, originator of the project, will exercise his talent as a continental chef. Mr Fankhauser’s qualifications include a Swiss Diploma and his confidence of success with the Chalet Rendezvous is so strong that he already contemplates extensions to the premises. There is ample scope for an additional block of bedrooms or the erection of residential flats on the lines of the two already provided. Plans also include lawn tennis courts and a putting green.”

The restaurant opened for business with a buffet lunch on a Saturday four days before Christmas of 1957. The mayor, Harry Barker, officiated at the opening amongst an invited crowd of local VIPs and well-to-do town-folk. While the Fankhausers stood in the limelight and were described in the local press as the proprietors, another man attended the opening that day, who had quietly and unassumingly partnered the Fankhausers in their bold endeavour.

A printed advertisement, what today would be called a 'flyer', promoted the newly-established business.

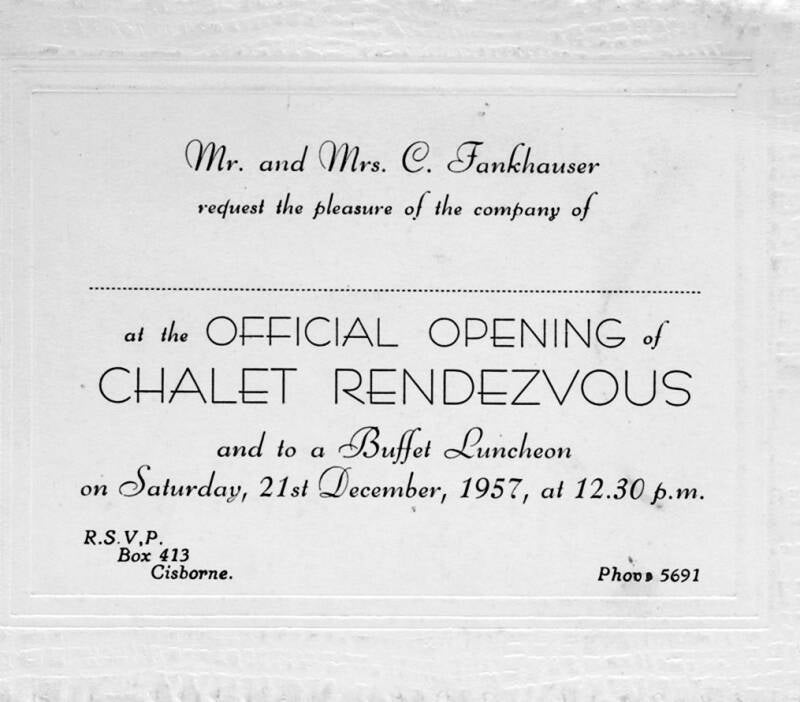

The best people in town were sent invitations to the opening luncheon held on Saturday, December 21, 1957.

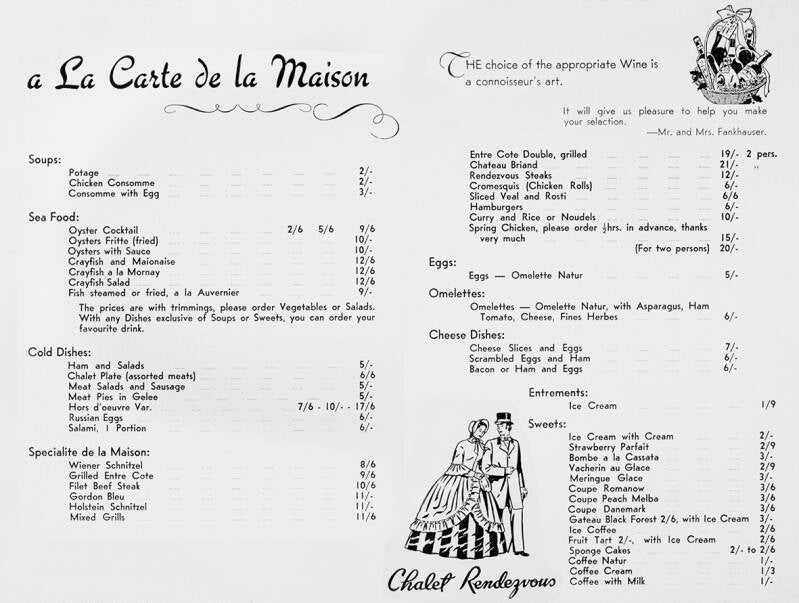

The first menu for the newly-opened beachside restaurant. A shilling was the equivalent of 10 cents. For example: Crayfish Mornay was 12 shillings and six pence or $1.25.

The Chalet was open for business from Christmas of 1957 and it quickly caught the public imagination. In 1958 Photo News was moved to write: “In the list of facilities and attractions which Gisborne can offer to the outside world, the Chalet Rendezvous at Wainui Beach, occupies a unique position. Set by the sea, backed by the hills, endowed with a beautiful building, luxurious guest quarters and a cuisine second to none, it is earning for itself a high reputation with visitors, many of whom have been from overseas. The Chalet is a dream come true for Mrs and Mrs C. Fankhauser whose efficient and hospitable management is not the least admirable feature of this unusual holiday resort. They have set out to create and have achieved something which blends the characteristics of their homeland, Switzerland, with the land of their adoption, New Zealand. This applies not only to the architecture of the buildings and its interior decoration, but also to the cuisine.”

In its own advertising The Chalet was cleverly positioned as: “Situated on the main East Coast highway with glorious vistas of golden sands, the blue Pacific and rolling green hills.” The menu was promoted as: “While standard New Zealand meals are available they are seldom ordered in the face of gastronomical delights of cuisine in all Continental variety. From Chateaubriand to Ravioli to Crayfish a la Mornay there is little the Chalet cuisine cannot produce nor is there any equal to the delicious Continental cakes and special ice cream confectionery appearing from the same source.”

It is of interest to note that in 1963 a dozen cocktail oysters could be ordered for 9/6d and a fillet steak for 10/6d. The much-lauded Chateaubriand for two was 21/-. A locally-caught crayfish meal was a mere 12/6d.

A 1950s Photo News feature titled “A Night Out At The Rendezvous”, where local couples “dressed up to the nines” are pictured dining and dancing, gives us a glimpse back at those times: “With fine cuisine, continental atmosphere and intimate surroundings, the Chalet provides all that is required to mark the occasional night out a great success.”

Lionel Neil is pictured at the piano, Owen Houlahan on the drums and guest vocalist Christine King “providing pleasing entertainment”. A photograph of a laughing line of pleasure-seekers carries the caption: “Custom at the Rendezvous demands that during the course of the evening, all present should take part in “La Conga”, an act in which all line up and dance single file over the dance floor, around the tables, and even through the kitchen.” On this particular night it “was discovered that Lesley Dunn and Jon Overbye were celebrating their newly-announced engagement and were toasted by all present.”

Long-time Wainui identities, Claire and Rob Bayly, both had an association with the Fankhausers. Not long after they had arrived in Gisborne from New Plymouth to start their nursery business in Lysnar Street a flood devastated the venture and to make ends meet Claire got a job at the Chalet, first as a waitress and then as a kitchenhand.

Claire says the Fankhausers had another foreign woman working for them named Helenora, who seemed to be part of the family. Claire remembers her first task on her very first night as waitress was to take out a tray of seafood cocktails. After a stumble the cocktails ending up all over the floor. “Never mind, Claire,” said even-tempered Mrs Fankhauser. “Carry on with your duties, but we’ll let Helenora take out the soups.”

Rob Bayly first met the Fankhausers when he tried, unsuccessfully, to dig a bore for water on the property. Rob says Charles was quite a character with an “eye for the ladies.” Hedy he remembers as a “very stout and very intelligent woman”.

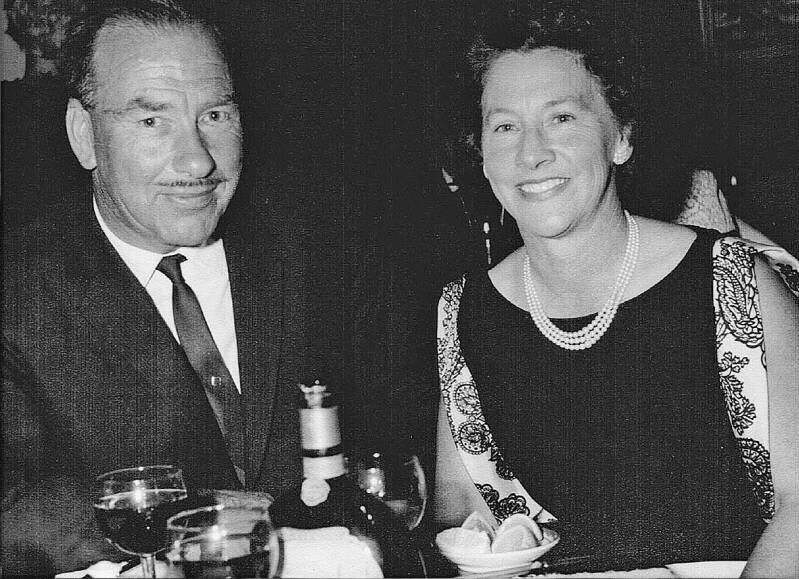

The Fankhausers behind the bar of their newly-opened Gisborne nightspot

At last the good folk of Gisborne had somewhere to get dressed up to have fun. Dine and dance was all the rage at the Chalet in the late 1950s.

The Graham Bell Combo was a popular dance band in the 1960s. Jim Nicklin on drums, Graham Bell on guitar, Bobby Bell the singer and Noel Bell on the organ. Right: Popular local pianist Lionel Neil kept the customers dancing.

With a licence to sell liquor the Chalet quickly became the place to go for a big night out.

Diners would form a line and dance 'La Conga' through the restaurant.

There has long been the assertion and assumption in Gisborne that the Chalet Rendezvous was the “first licensed restaurant in New Zealand”. Along with the “world’s first sunrise”, the Chalet’s “first restaurant” claim is part of our local folk-lore, and almost essential to our city’s self identity.

On September 8, 1957, three months before opening, the Chalet’s lawyers, Nolan and Skeet, assisted Fankhauser as the company’s nominee, to apply for a Tourist-house License, under Section 57(2) of the Licensing Amendment Act 1948. When the Chalet opened in December of 1957 it was ready with a bar, fully stocked and ready to legally serve wine, spirits and cocktail drinks to dining guests. It was therefore the first restaurant in New Zealand to have a license to serve liquor.

A “tourist-house” in those days generally meant a hotel-type establishment at a tourist destination, such as the Chateau Tongariro. These businesses were not hotels with public bars as such, so a special licence was necessary to allow the sale of liquor to house guests in dining rooms. A Tourist-house licence allowed the serving of liquor under two clauses: (a) To any person who is for the time being a lodger, for consumption on or off the premises, at any time on any day. And, (b) to any person partaking of a substantial meal on the premises, in any place or room (other than a bar) used for dining, for consumption as part of the meal from 9.00am to 11.30pm on any day.

Tourist-house licences had been available for some years, but the assumption can be made that the Chalet was the first to apply the “Tourist-house” definition to, what was in 1957, a rather unique business concept.

The word “restaurant” was itself a new concept in New Zealand and only a few dining establishments, usually in the main centres, described themselves as such. Early restaurants in the main centres were not involved in providing accommodation, so had no legal recourse to a tourist-house licence. At the same time “motel”, the new buzz-word for a motor-hotel, was also a relatively new concept in this country, recently copied from the United States to cater for a newly mobile, motoring population. The Chalet Rendezvous was designed to be a blend of the two new trends.

Fankhauser’s design of a large downstairs dining room or “restaurant”, with four modest guest bedrooms upstairs and two small separate “tourist flats” behind, was unique in this country at the time, and made it possible for its lawyers (Nolan and Skeet) to present the business to the licensing authorities as a “tourist-house”.

So the reality is that the Chalet opened for business in 1957 with a “tourist-house licence”, definitely not a “restaurant licence”, as no such thing yet existed. But the Chalet was, we believe, the first hospitality business in New Zealand to cleverly use the “tourist-house” definition to run a complimentary part of its operation as a “resttaurant”, and therefore the claim of “first licensed restaurant in New Zealand” can be made, if by that we mean the “first restaurant in New Zealand to have a licence to serve liquor”.

However! Outside of Gisborne it is widely recognised that pioneering, Dutch-born, restaurateur Otto Groen received the first-ever “Restaurant License” for his Gourmet Restaurant in downtown Auckland in 1961. Otto Groen spend several years lobbying, petitioning and appearing before select committees to bring about a change in the liquor licensing laws.

After an amendment was passed, by the Walter Nash Labour Government, the licensing commission proceeded cautiously, issuing only an initial ten licenses to restaurants in the main centres. Otto Groen has long held the claim to obtaining the first Restaurant License in New Zealand. He has photographs and clippings from Auckland newspapers, of the then chairman of New Zealand Licensing Commission presenting him with the license over a glass of champagne at a celebration of the event at the Gourmet Restaurant on December 13, 1961.

BeachLife spoke to 81-year-old Otto Groen in 2009, who was gthen still in the hospitality business in Auckland as head of a private training school for hospitality workers. Surprisingly, he had never before heard of the Gisborne claim to his most-coveted achievement. The convivial restaurater was amused and bemused to be told of the Chalet’s long-standing claim to his famous accolade, but agrees with this writer’s above conclusion that the Chalet’s “tourist-house licence” may have been popularly misrepresented over the years as a “restaurant licence”.

So the Chalet Rendezvous at Wainui Beach may not have technically been the first restaurant to obtain a Restaurant License, but it’s almost certain it was the “first restaurant in New Zealand to have a licence to serve liquor”, beating the celebrated Mr Groen to a celebratory round of drinks at the bar by four years.

The Fankhausers remained at Wainui Beach until 1964 when they sold their share of the business and moved on. What eventually became of the Swiss couple is not completely clear despite wide-reaching research. There is a suggestion that they may at one time have run a restaurant in Auckland after leaving Gisborne. They did surface again briefly in 1979. Living at Matakana, north of Auckland, the couple tried to persuade the New Zealand government to take on one of Charles’ creamy dessert recipes as a potential export item.

Always quick to see an opportunity, Charles sent off an invitation to sample his new Cream Cheese Cake to the then Prime Minister, Rob Muldoon and wife Thea, who had a holiday home at Hatfield’s Beach, not too far from where the Fanhausers were living near Matakana. Thea Muldoon replied from Vogel House on September 10, 1979: “Dear Mr and Mrs Fankhauser. Thank you for offering to let us sample your cheese cake at Hatfields. I regret we do not find time to visit Hatfields very often as we are now resident in Wellington. I have referred your letter to the office of the Minister of Agriculture for his attention. Sincerely etc.”

The Fankhausers settled on a secluded country property on the Leigh Road overlooking Little Barrier Island north of Matakana. The property was sold through a trustee in the mid ‘90s after George Fankhauser was physically removed from the house and taken into care. It is believed that after his wife died he became a recluse.

Kay and Lu Rathe of Point Wells, investors who bought the Fankhauser property from tghe trustee say it was in an appalling state – a once lovely garden had become completely inaccessible and the house had become sealed off by overgrown ivy. Inside it was rat infested, full of old newspapers and hoarded belongings. We have not been able to find out what became of George Fankhauser after he was taken from the Matakana house.

CHAPTER TWO: A trip down memory Lane

As the Fankhausers departed for Auckland the concept of a Swiss alpine restaurant – where nights out were often orchestrated with a Bavarian beer hall flavour – was beginning to wear thin. Restaurants by nature have their ups and downs and Bill Williams may have believed the business needed a new style of management after the depature of the Fankhausers, if it was to progress and continue being popular and profitable.

In the early 1960s Bill Lane, “tall, dark and handsome” and a member of the prosperous Lane’s Hosiery family from Levin, was running a highly-successful restaurant in the Waitakares, just out of Auckland. It went by the heady name, Back of the Moon. It included a 100-seat dining room and was promoted as a “dine-and-dance” establishment – an “exciting, new, European concept” in the days when dining out in New Zealand usually meant steak and eggs with a pot of tea at the local grill.

Back of the Moon had a full dance floor. The celebrated jazz band, the Crombie Murdoch Trio, played every Saturday night. While liquor was “strictly forbidden”, the reality in those days was that the women would smuggle bottles of whisky hidden in their fur coats. BYO wine was secretly chilled and served stealthily by a waiter in a long coat.

Bill Lane had built the business up since arriving from Wellington in 1951 and had become a leading light in the Auckland hospitality industry, eventually president of the Restaurant Proprietors Association.

In 1963 Lane regrettably has to hand over the Auckland restaurant to his first wife, as part of a marriage break-up settlement, and came to live in Gisborne with his new partner and later wife, Kathleen. He became known to local businessman, Jack Howard, who helped him get a job running the new coffee shop at the revamped Gisborne airport terminal.

Liking his style Howard later engineered a meeting with Bill William’s representatives to see if there was a way the worldly and debonair Lane could take over the running of the Chalet Rendezvous. The result was the Fankhausers being bought out and the creation of a new company called Chalet Rendezvous (1964) Ltd, with Lane as an equal partner.

1960s Chalet owners Bill and Kath Lane enjoy a night out themselves over a bottle of Mateus Rose.

Lane had a new kitchen was built, a new bar put in at the front of the dining room, more accommodation was built and Lane set about resurrecting the Chalet Rendezvous as a highly creditable dining establishment.

Visiting dignitaries and politicians would book their accommodation and meals at the Chalet. It was often booked, particularly Saturday nights, as far as three months ahead, seating up to 100 dining guests each night. It was “the place to be, by the sea”.

Lunches were served each day and the Sunday smorgasbord (an exciting new European dining concept) was a popular event each weekend. Jean Hawksworth was the day cook who prepared lunches over a four year period during this era. Chefs of note were a J. Spencer-Standing and Terry Knight.

In 1967 an oyster or crayfish cocktail was priced on the menu at 75 cents. Soup would set you back 35 cents. A T-bone steak was $1.65 and fillet mignon with mushrooms was $1.90. Chateaubriand, the Chalet special, a whole beef fillet with port wine and bacon and bernaise sauce was now $5.00 for two people. On the wine list were imported choices including Schloss Johannisberg, Chateau La Fontaine, Cruse Monopol Bordeaux along with McWilliams Bakano and Cresta Dore, Blue Nun Liebfraumilch, Chianti, Orlando Barossa Pearl and Penfolds Chablis (all supplied by Williams and Kettle and sold at double the wholesale cost). The Chalet was open every day from 6.30pm till the technical closing time of 11.30pm.

The licensing laws were seldom policed and guests were welcome to stay until the small hours. Drinking and driving was not seen as a serious issue in those days. Bill Lane, who BeachLife interviewed for this story by phone at his home on the Gold Coast (in 2009 and was then alert and very much alive at nearly age 96) said: “There was never any trouble with the law, if the guests wanted to stay we just kept on going. Gordon Wattie used to come for dinner most Saturday nights and then call back on Sunday to pick up his car. We had lots of company functions. The Watties’ executives would come for lunch meetings, Fisher and Paykell people, including Sir Wolfe Fisher. Cabinet ministers stayed, Lord Vesty used to call in regularly. It was a great time with many out-of-town travellers calling in and local people having special functions. It really was a great time, full of nice happy memories.”

The Chalet was certainly well ahead of its time. In the 1960s there were few other choices for dining out apart from the dining rooms of the local hotels. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the new concept of “bistro-style” restaurants appeared in Gisborne.

By the early 1970s Bill and Kathleen were tiring of the long nights and, by taking regular holidays there, had grown fond of the Gold Coast of Australia.

The Chalet's menu in the 1970s featured crayfish and oyster cocktails at 75 cents, chicken chasseur at $1.80, T-bone steak at $1.65 and , f you were really wanting to impress you date, Chateaubriand, fillet steak and bacon in a béarnaise sauce for two at a pricey $5.00.

One day while Bill was mowing the lawns and thinking about the warm Australian beaches, a “big flash car” pulled up and a real estate agent from Auckland said he had a client interested in buying the business.

It was 1972, Ivan Hawkless, originally from Taumaranui, came to town and set about running the Chalet Rendezvous, retaining most of the staff from Bill Lane's regime. Waitresses were Honey Bryan, Helen Humble, Pat Flockart, May Dayberg. Bill McMurray was the wine waiter and in the kitchen were chefs Terry Knight and Oliver Pasquale. Terry Knight later opened the Friar Tuck (later The Balcony) restaurant in Gladstone Road introducing the concept of meals on hot cast-iron plates.

Waitress Honey Bryan, the daughter of well-know local pharmacist Alistair Bryan, remembers the time vividly: "It really was the place to go in Gisborne. The dance floor was packed every night, everyone dressed up in their best outfits. There was a full a la carte menu. I think a steak meal was about $1.95 and a shrimp cocktail about 90 cents. We had all sorts of things happen out there. Lots of scandals and goings-on, but all-in-all it was mostly just lots of fun and laughter, dancing and singing. It was very upmarket, the place to be. It was actually the only place to be in Gisborne.

"Every Saturday night the place was packed. Through December and January the motel and the restaurant would be booked out nearly every night. We had a resident band, the Graham Bell Combo, which featured Graham Bell, brother Noel and his wife Bobbie Bell and Owen Houlahan on drums. Tony Beattie took over when Noel left for Australia and Lena Ruru was often also a guest pianist."

Love was in the air not long after Ivan showed up at the Chalet and he soon fell for the pretty 22-year-old waitress. He then separated from his wife who had returned to live in Auckland and he later married Honey in December of 1975.

Ivan and Honey operated the Chalet together for going on two years and then headed off to Tauranga after which the Chalet went through a period of short leases. In December of 1973 the building was leased to a McCormick Enterprises Ltd. Eighteen months on, in July of 1975, the lease was transferred to G. F. Faulkner Ltd, then in July of 1977 to P. G. White Ltd and again in November of 1978 to Cameron Homes Ltd of Tauranga.

There are stories that the legendary hardman, Kimball Briscoe Johnson, lived in one of the back units during this era. Hawkless added to the Chalet title by purchasing the section on the south side of the site during this time.

By 1981 Ivan and Honey had lost interest in keeping the Chalet and were ready to sell. They bought an orchard and moved to Tauranga where they made other property and motel investments over the years. Their time at the Chalet was done and a new era was about to begin.

CHAPTER THREE: Malcolm in the middle

In 1981 a charming and rather colourful entrepreneur turned up in Gisborne who was to play the next lead role in the ongoing saga of the Chalet Rendezvous. Malcolm Sutherland McArthur was a dairy farmer from Waihi when he decided to move to Gisborne with his second wife Annette and his 13-year-old son Trevor. The title was transferred into his name on the 2nd of December, 1981. Malcolm made a clean swap of his Waihi dairy farm for the Wainui property.

The popularity of the Chalet had started to wane during the late 1970s but McArthur quickly reintroduced good service practises in the restaurant, employing a top European chef and professional front of house staff.

Malcolm McArthur and his wife Annette with staff members who managed the complex in their absence, Leigh Schroder and Megan Johnstone, in the early 1980s.

The large dining room was soon at full steam again. Charismatic, intense, quick-witted and generous McArthur would steer the Chalet through a boom period for the next three years.

This writer was also one of the many who worked at the Chalet during this period. My job was barman and wine waiter on the busy Friday and Saturday nights and on the many other week nights when the house was full for functions. Other locals who worked at this time were waitresses Leigh Schroder, Jill Simpson, Linda Coulston (then Foreman) and Sheree Drummond.

Robyn Barker (then Pere) worked in the kitchen for a period. Mark Barker worked with me at the bar and wine waited the tables, serving Malcolm’s then comprehensive selection of imported and New Zealand wines, which were stored in a fabled “secret” cellar beneath the old bar. This was a great place for a sly slug from a returned half-full bottle of Liebestraum or some other wine of the day. Nearly all former staff members remember fondly the huge bowl of Bluff oysters which sat just inside the kitchen chiller. Malcolm himself would show off by dipping in for a fistful now and then. So the cooks, kitchen hands, waitresses and bar staff alike decided the delicacies were fair game when work duties took them into or even near the chiller.

Waitress Megan Johnstone dressed in her traditional Swiss waitress outfit in the early 1980s.

Local girl Leigh Schroder (later Dawson) who had recently returned from working at the Wrest Point Casino in Tasmania, worked for the McArthurs through this period as hostess and later manager. Megan Johnstone of Douglas Street, worked part-time as head waitress and maitre de when needed.

As Leigh Schroder confirms, these were “great times” both during and after hours at the Chalet Rendezvous with the young staff efficiently serving well over a 100 guests each night, often in the McArthur’s absence if they went out of town or needed a night off.

Malcolm was an excellent and convivial host, larger than life at times but fastidious about providing excellent service in all respects to the hundreds of Gisborne and Wainui folk who flocked there not only to sample the fine menu but also to enjoy the festive, lively atmosphere of a restaurant operating at near full capacity. Many Friday and Saturday nights were fully booked with the Chalet serving up to 160 diners.

A house band played throughout these years. Terry Sheldrake with Tama Koia and John Wilson were a three-piece called “Motion”. Sheldrake would play the piano on his own on quiet nights, but once the bookings got over fifteen, Malcolm would insist on calling in the full band. Later on the band was “Sapphire and Steel”, consisting of Graeme Swan, Kate Smart and Dein Ferris.

The band boys and the waiting staff were easily persuaded to stick around for the after hours socialising with Malcolm who generously and enthusiastically officiated over most of the regular late night lock-ins.

While Malcolm’s generosity and desire for company was eagerly taken advantage of it was seldom outrightly abused.

However, assistant cook of the era, Ashley White, remembers a particular night when Malcolm singled him out for an extended rum-drinking session with an unspoken challenge to see who would be the first to drop.

One of the traditions of a Malcolm McArthur-binge was that the fellow-binger had to “shout” – which meant going to the bar to pour the drinks. (The drinking sessions were usually held around the prep table in the kitchen out of view of passing traffic.)

Unbeknownst to Malcolm, young Ashley was infamous internationally for his binge-drinking exploits. Every time he set up the triple-shot rum-and-cokes for each “shout”, Ashley would help himself to a sneaky shot or two of “top shelf” liqueur. Shortly before sunrise the proprietor collapsed snoring at the table. Ashley went to the bar, put his feet up and enjoyed the sunrise while helping himself to a couple of night caps from the top shelf before shaking Malcolm awake up around 8.00am.

“Don’t let Annette see me like this,” Malcolm mumbled, as Ashley assisted his boss down the highway to his nearby Moana Road flat, depositing him safely on his couch with a blanket, where a worried Annette found him later in the day.

On another occasion, being New Year’s eve night of 1983, bar and kitchen staff and members of the band, on Malcolm’s invite, stayed on drinking till the sun rose on New Year’s day. A spontaneous, naked, group exodus for a celebratory swim at the beach across the road occurred at sunrise. Meeting milkman Lex Gibson coming down Moana Road on dawn deliveries was funny enough until Malcolm himself made a late dash across the road to the beach, stark naked except for a black bow tie. (Photos do exist but have never been published.)

Malcolm was legendary for these late night shenanigans but unfortunately they were not the best thing for a man with a dodgy liver. He was often in pain, sometimes very ill, spending time in hospital and at times had to go away on recovery vacations.

During these absences the Chalet was at first entrusted to retired Wainui businessman Win Ellis, who had been a great friend of Bill and Kath Lane and then the McArthurs. Later on Leigh Schroder and Megan Johnstone were given charge. They ran the ship admirably, including looking after Malcolm’s teenage son Trevor.

However there was the odd night when there were no bookings and the girls would shut the doors to the public, wheel out the BBQ, put the call out and throw a grand private party for their wide and eager group of friends. Trevor and his high school mates were given access to the beer fridge and kept occupied with their own party upstairs.

During this era the motel units were working well and even on week nights the bar was busy entertaining the many sales reps who chose to stay in the units, most of whom would end up having late night drinking sessions with Malcolm and the chefs of the day. Front of house staff wore black and white, the wine waiters bow ties, the waitresses traditional Swiss-style uniforms, the chefs white hats. In the early McArthur years the kitchen was ruled by a highly-qualified Swiss chef who was largely responsible for the ongoing popularity of the restaurant.

Peter Britt had come to New Zealand in 1968 from Switzerland and first worked at the THC Wairakei resort. He discovered Gisborne on holiday and ended up some time later getting a full-time job with the McArthurs. He says it was just an amusing coincidence that a Swiss cook ended up working at a “Swiss chalet” in New Zealand, but it certainly added to the appeal of the restaurant to be able to boast of an authentic, and highly-rated, Swiss chef.

Manager Leigh Dawson remembers the McArthurs running a very fine establishment with the assistance of Peter Britt: “We had various elaborate set menus for corporate dinners, and a full a la carte menu. Peter Britt was a great chef.”

Other chefs from this era included Peter McNamarra and Dave Barron. Barron and Britt left the Chalet at the end of 1982 to open Flambards in Childers Road. Other chefs were later employed, but possibly none measured up to the culinary flair of Peter Britt and The Chalet may have begun to lose its lustre after his departure.

Staff were amazed at one time when the man convicted, then later pardoned, for the Crewe murders, began showing up at the Chalet.

Malcolm had grown up with Arthur Allan Thomas and had been a big supporter of his retrial bids which led to the Royal Commission that found him innocent. Malcolm invited Thomas and his new wife to the Chalet on more than one occasion, to relax and possibly hide away from the limelight for a while.

Leigh Dawson remembers him coming to stay: “He was very shy but really nice. The McArthurs were really good friends of his and he came and stayed quite a bit.” Another former staff member said Malcolm once told him he had been the “bank roll” behind the Thomas retrial campaigns.

Another historic social occasion at The Chalet was the famous “wrap party” at the end of the filming in Gisborne of the movie The Bounty, directed by Roger Donaldson, starring Anthony Hopkins, Mel Gibson, Daniel Day-Lewis, Liam Neeson and a gang of other lesser known movie stars of the day. The Chalet connection began with one of the chefs of the time, Peter McNamarra of Makorori, catching up with Mel Gibson, who he had been to school with as a kid back in Sydney.

Gibson started coming out to The Chalet for dinner most nights, bringing his wife Robyn and their children. Leigh Schroder would take the kids upstairs where they could watch TV until their parents were ready to go back to their accommodation in town.

Along with being the best place in town to have a function at the time, this led to The Bounty producers hiring the Chalet for their end-of-filming celebration. It was a famous affair with just about everyone involved in the filming – the stars, the local helpers and “extras” and even the local fire brigade (who had used their hoses to simulate a storm at Cape Horn) – turning up for an all-you-could-eat-and-drink Hollywood-style binge. The big “do” was put together by Malcolm, Annette and staffees Leigh Schroder and Linda Foreman (later Coulston).

This was the infamous occasion where this writer (who was working part-time as a wine waiter at the Chalet at the time), sneakily gate-crashed the party through the back kitchen door. After I took a posed snap of Mel Gibson and the film's director Roger Donaldson with two of the Tahitian girls who were extras in the movie, Gibson, who knew I was a photographer for the local newspaper, decided I was an untrustworthy “paparazzi” and demanded that I leave. Attempting to placate the volatile actor to avoid eviction led to a classic bar-room brawl between myself and Gibson. Fists were thrown (none really connected) and we ended up in a wrestlers’ clinch, crashing about the lounge bar, knocking over tables and chairs, smashing glasses until the crowd jumped in and pulled us apart. Needless to say it was me and not Gibson who was tossed out the front door (by the treacherous local firemen!).

The photograph this author took of Mel Gibson, pictured with film director Roger Donaldson (right) and Tahitian extras during the filming of The Bounty in Gisborne, which led to an infamous bar room brawl at the Chalet Rendezvous in 1983.

Leigh Schroder’s memory of that night is helping Malcolm in the kitchen stirring up gallons loads of maitai cocktails in plastic buckets. It was possibly the biggest party ever seen in Gisborne in terms of celebrity “who’s who”. It is believed others ended up facing the “Mad Max” side of Mel Gibson’s personality as well that night.

Transient chefs, new restaurants in town, the new stringency of drink driving laws and Malcolm’s ongoing health and financial problems all contributed to the Chalet’s downturn from about 1984 on. In October of 1984 McArthur had to get away for a while and leased the Chalet to a messrs Sims and O’Connor, two men from Auckland, ostensibly for a period of 16 years. A property in Mangere was part of the deal. Not much is known about this partnership as the couple stayed only a matter of months, the lease transferring in May of 1985.

With the business up for lease the first McArthur years came to an end with Malcolm and Annette heading off to live in Auckland. Son Trevor had grown up to call Gisborne home and, after leaving school, stayed on to become the service manager for the Enterprise Motor Group (at time of writing in 2009).

CHAPTER FOUR: Pizza nights and no shrinking Violet

In 1985 Violet and Allan Foubister were a successful business couple living in Auckland. After three years OE, working and saving money in South Africa, they had a freehold Auckland home, a boat and a bach at Piha.

They had just sold a fruit and vegetable business at St Lukes shopping centre and Allan was trying out a new business installing Para Pools. However, they were restless and in need of a new adventure. After a visit to the Bay of Islands they caught the romantic dream of running a beachside holiday resort. As chance had it they saw an advertisement in the New Zealand Herald advertising the lease of the Chalet Rendezvous, so they came down to check it out.

They loved the beach but at first they turned down the prospective deal as the Chalet needed maintenance work and the deal offered to them just “didn’t feel right”. But Malcolm McArthur was a persistent and compelling salesman. He pursued the couple in Auckland finally signing them into a lengthy lease, on May 25, 1985. Violet and Allan Foubister, both then aged 37, with little hospitality industry experience, sold their home and left Auckland with their six-year-old daughter, Amanda, bound for Wainui Beach.

At first it was the realisation of the “romantic dream”, running the quaint, Swiss-style establishment overlooking the surf . “We were captivated,” says Vi. “We met such lovely people and were drawn by the energy of the place. Even though things later went very wrong, I think it was all supposed to happen.”

Things went awry from the very first week when one night, with the restaurant fully booked for the first time, the chefs didn’t show up. “It was a nightmare,” says Vi. “We kept a straight face out front while there was absolute chaos in the kitchen, but somehow, with the waitressing staff pitching in, we got through.”

She also remembers the place being very run down and needing much maintenance. There were plumbing problems, recarpeting, rewiring – and the lease stated such things were the lessee’s responsibility. They put a “pile of money” into the business by enclosing and finishing off a swimming pool area Malcolm had started on the spare section next door and establishing an outdoor garden-bar overlooking the beach. They also redesigned the units increasing the number available from 8 to 13. Income from the motel units was crucial to keeping the business afloat. The rent was huge, but to make a go of it they were committed to putting things right, and eventually spent all their savings. They had sold their Auckland property to buy into the lease but steadfastly held on to their bach at Piha, which was later to prove fateful.

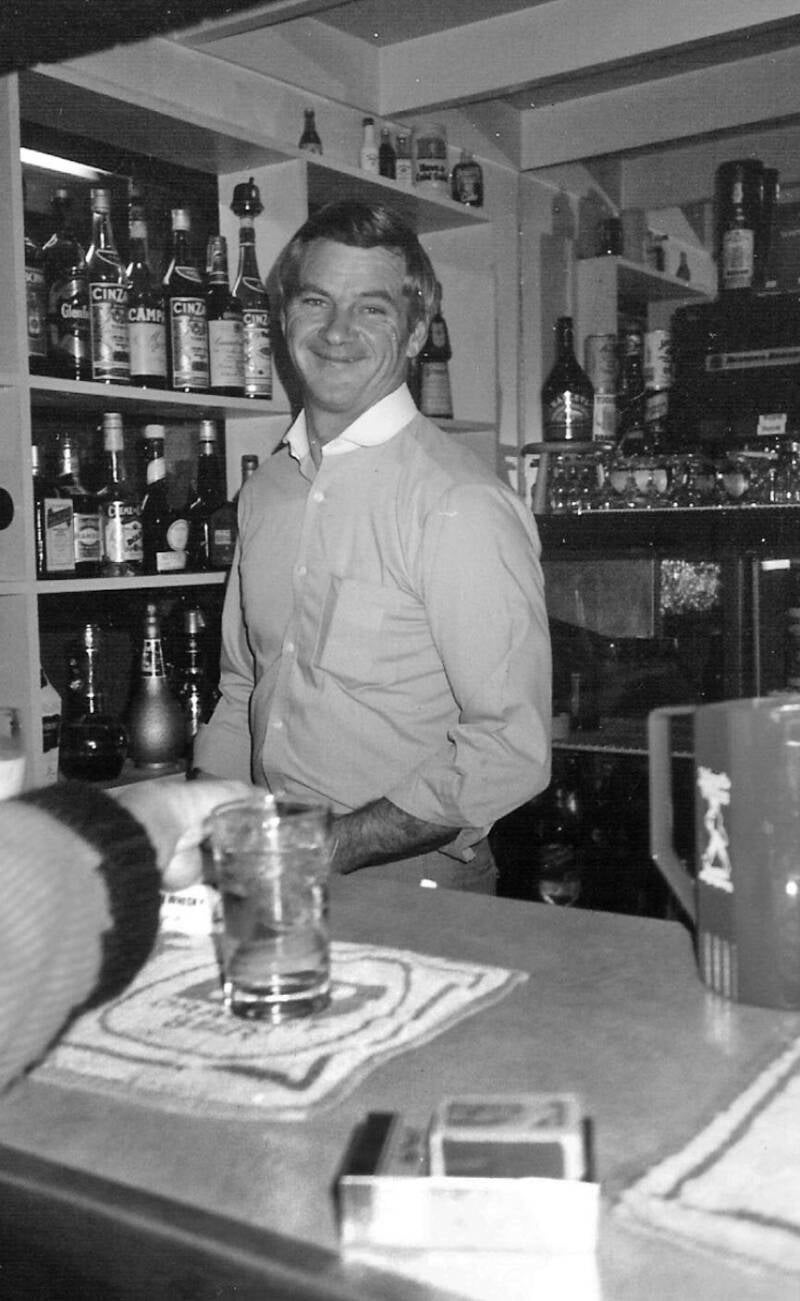

Owner Allan Foubister tending the bar at the Chalet in the mid 1980s.

Things started to go really wrong when, in mid-1987, Allan Foubister nearly lost his foot in a lawnmowing accident. His recovery took nearly six months and during that year Vi could see the business going downhill. Their desperation to make ends meet led to a legendary era at the Chalet known as “Thursday Nights”.

The restaurant licence meant they could serve people at the bar till the early hours as long as they had partaken in a substantial meal. So Vi advertised an “Italian Buffet” (pizza) at $15 per head which started around 11pm each Thursday night after any regular evening diners had left. The idea was to attract the passing crowd, literally, vacating the nearby Tatapouri Hotel and looking for somewhere to “party on”.

The concept caught on and the Chalet soon became the mecca for “night owls” from town as well as those heading home from a session at the nearby Tatapouri – the seaside pub enjoying an institutional “huge” Thursday night before the 11pm shutdown. Vi would regularly see the last of the revellers off the premises not far from sunrise. One legendary night saw Todd Casella bring Herbs to the Chalet with Joe Walsh (ex Eagles) in tow. Through all the ups and downs Vi was a serene host, immaculately dressed, calm and polite, even when dealing with some of the town’s most prodigious “party animals”.

During this era, on or about July 1, 1988, Allan Foubister drove himself to Auckland and took his own life at the Piha bach. Shocked and bereft, Vi was left to trade on, trying to keep the Chalet business afloat. She says she could not have survived without the help of her staff, particularly local girl Jill Simpson who took over looking after the books while Vi looked after front of house. She was also well supported by others including Sandy Kokiri, Christine Breingan, Carole Green and Chrisse Robertson.

The business carried on through to 1989 but eventually it became just too tough. One day, after she had paid all creditors, Vi tidied the place up, shut the doors and departed without looking back. “What happened after that I have no idea, I walked away and that was that,” she says.

While the Chalet days were done and dusted Vi could not break her ties with Gisborne. She had earlier started a loving friendship with charismatic Matawhero winemaker, Denis Irwin. They married and together they ran the Colosseum Restaurant and Bridge Estate caravan park at Matawhero for a time

After a serious car accident, they sold the Matawhero property and planted a small vineyard to supply their new label, 747 Estate Winery. Denis died on April 10 2020 after a battle with bone cancer.

Violet and Denis Irwin. Photo taken by wine reviewer Bob Campbell.

CHAPTER FIVE: McArthur returns and gives Moodie the blues

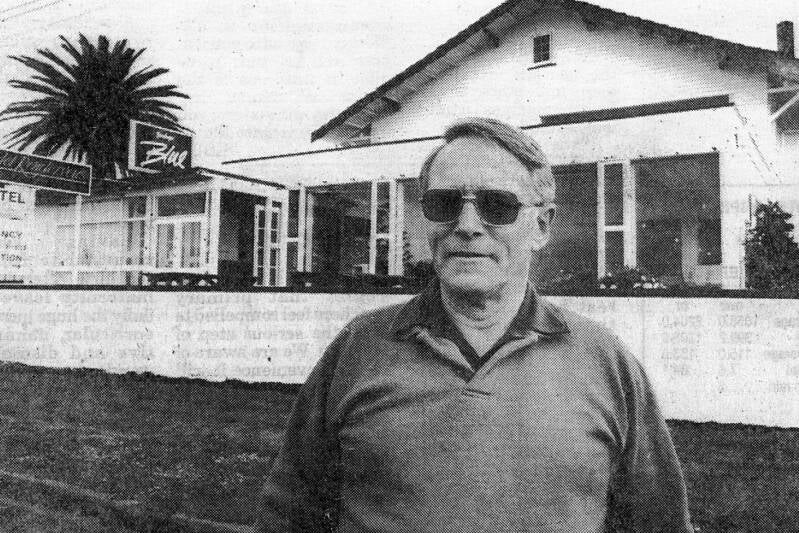

Auckland property investor Neil Moodie, who spent a decade protecting his investment in the Chalet Rendezvous, pictured outside the restaurant in 1994.

During the Foubister lease period an Auckland builder and property investor named Neil Moodie came into the picture. In 1985 Malcolm McArthur bought an attractive five-bedroom, harbour-view property Moodie owned at Hobsonville. As part of the deal McArthur provided a property he owned at Blackbridge, Mangere, as the deposit. McArthur had earlier taken this as part payment on the Chalet lease from his former lessees, Sims and O’Connor. Moodie didn’t know it at the time, but this deal was to be the beginning of a decade long legal marathon involving mortgage battles, bank disputes and his eventual ownership of the Chalet Rendezvous.

In 1987, when McArthur needed to sell the Hobsonville property to meet mortgage repayments on the Chalet Rendezvous, Moodie ended up holding a $95,000 second mortgage on the Wainui property, then worth around $1 million. It was the beginning of a complex saga of caveats, mortgage transfers and an eventual mortgagee takeover of the property. This at a time in 1987 when mortgage interest rates had reached 18 per cent.

After Vi’s sudden departure the Chalet was closed for a while which drew the attention of the local press. The Gisborne Herald made enquiries and ran an article headlined, Future Uncertain for Gisborne’s Oldest Restaurant: “The fate of Gisborne’s oldest restaurant, the Chalet Rendezvous, a pioneer licensed restaurant in this country, hangs in the balance. It is understood the Chalet has been on the market for some months and is closed at present.”

McArthur was located in Auckland: “Mr McArthur confirmed he was open to offers for the Chalet but in the meantime he intended to open it for business again as soon as possible. The current tenant had left abruptly and the restaurant has to be open again as soon as possible to meet the license requirements. He said he would return to Gisborne to run the business himself, as he had done from the time he bought it in 1980 until 1984 when the leased it out.”

Like his namesake, McArthur did return, albeit briefly. The Chalet opened for business again in November of 1989, securing the services of a young Hong Kong-born chef, Stanley Choy. Sporting top credentials from London, and “direct from the Regent in Auckland”, Stanley “added an oriental touch to his classical French training and created a menu appropriate for Gisborne.”

The Chalet hung its shingle on its chef’s shining star in 1990 when the Claridges-trained chef won the annual New Zealand Meat Producers Lamb Cuisine Award with a dish called “Chinese Lamb on Bone”, a traditional lamb-rack served with an oriental flavour.

The Gisborne Herald was moved to write: “To have reopened in trying conditions, to have raised the standard to what it once was and earn not only a Lamb Cuisine Award, but also a Taste New Zealand Award, in just over six months, is evidence enough of the McArthur’s reputation for providing only the best to patrons.” The Herald went on: “It brings a return to the magic that past patrons of the Chalet Rendezvous remember so well. With Malcolm and Annette McArthur back to welcome diners once more, the crowds are slowly flocking back. With a shuttle bus service on offer from town to Wainui every night there is no excuse not to travel the extra distance.”

Nelson Gooding, who owned Fettuccine Brothers at the time and also employed Stanley Choy, says: “Stan the Man was a real character, a Chinese with a cockney accent. He’d have five tea towels hanging off his belt and a pint of beer in his hand at all times.”

While the press reports gave an impression of the Chalet getting back up to speed, the McArthur’s finances must have been in some jeopardy at this time. Title deeds show the Chalet taking out mortgages with various banks and finance companies during the ‘89-‘93 period.

In 1989, with a vested interest in keeping the business going, Neil Moodie took over a fourth mortgage which, combined with a second mortgage from the Hobsonville property deal, gave him a big stake in the McArthur-owned property.

Moodie ended up in a dispute with the Westpac Bank over who held the first mortgage (and also the National Bank over a security for around $40,000 they had given to McArthur over the Chalet’s chattels, which the bank later seized and put in storage). Moodie, who was trying to organise a mortgagee sale, vehemently disputed the legality of this.

Without any furnishings or kitchen equipment the Chalet could not be sold at a realistic price. An auction was aborted and the business was forced to cease operating for a period of nearly two years from 1992. In 1993 Moodie called a meeting with Westpac and National Bank representatives, sorted out the chattels dispute and gained the right to step in to run the business as mortgagee in possession. He structured a deal with Westpac to take over McArthur’s first mortgage and then took over the title, thus ending McArthur's eventful ownership of the Chalet Rendezvous.

The chattels were returned but numerous items were alledgedly missing or had been ruined according to Moodie. But despite the obstacles he set about refurbishing and re-establishing the Chalet as a going concern.

In early ‘93 Moodie put a manager into the business and entrusted a Gisborne accountant to look after the finances and generally keep an eye of the place while he returned to his affairs in Auckland.

However, Moodie says the observant accountant drove by one night and noticed the back motel units had their lights on most of the night with cars coming and going till the early hours. The accountant also knew there was no money coming in from rental of the units.

Moodie says: “When I was alerted to this, I drove down the next day and went into the office while the manager was out and printed off the telephone records for the back units and saw that there were hundreds of calls being made. When the manager returned I confronted him about the mystery phone calls from the ‘empty’ units. At first there was denial but he eventually came clean about the sort of ‘profession’ he was running from the rooms, after which he was quickly shown to the door.”

Moodie reluctantly stayed on to get the business going again while looking around for someone to lease the Chalet on so he could return to his wife and his retirement in Whangaparaoa. In late ‘93 he leased the building and business for a first term of four years to Grant Kennedy and Greg Ginn, the latter a former Gisborne man who had returned from some time living overseas. When Kennedy pulled out, Ginn then invited in his friend Ross “Charley” McLeod.

In 1993 local girl Debbie Wooster was working as a conference and wedding planner in Melbourne when she got a call from Charley asking her to come home to manage the running of the Chalet. Debbie was flown home, given accommodation at the Chalet and from where she made a concerted effort at marketing the restaurant back to its former glory.

Fine dining and quality service was once again the promise made to prospective Gisborne diners. Lunch being served from 11am to 2pm and dinner from 6pm to 10pm. Debbie manage3d the business for nine months before leaving for a new job, at the luxury Wigwam Resort in Phoenix, Arizona.

During this time and after her departure the Chalet had become more and more a local club house for Greg, Charley and their wide and colourful group of salubrious friends. Eventually Ginn and McLeod made departures from the Okitu address and Moodie was forced to return to Gisborne once again to sort the place out.

Charley McLeod, Debbie Wooster and Greg Ginn ran the Chalet for a time in the early 1990s.

The sudden closure of the restaurant and Moodie’s subsequent arrival back in town was noted by the Gisborne Herald. An optimistic caption of Moodie standing outside the Chalet read: “Chalet rendezvous owner Neil Moodie of Auckland says the latest setback to the complex is a challenge. He aims to have the business running better than it was before.” The article went on to say: “The Chalet has had a chequered history with several changes of management and lessees in the past few years coupled with a number of closures.” Moodie said: “I would like to see the business established on a sound basis. It’s a fantastic location. All it needs is the right operator. I hope the future will be brighter than it has been. I hope it will change its downward course.”

Moodie spent 1994 and 1995 at the Chalet running the restaurant and the motel units himself, calling in chefs faor the dining room as needed. He remembers catering for several wedding receptions and large functions during this period: “I had some real good people helping me out. Everyone enjoyed themselves and had a real good time.”

But Moodie was keen to see the back of the place. In 1996 local lads Riwai Williams and Takapuna Mackie approached Moodie, worked out a deal and bought the Chalet Rendezvous. However, by leaving money in as vendor finance, Neil Moodie’s fun and games with the Chalet were not completely over.

CHAPTER SIX: Tropical Ambrosia and a Wild West Show

Sensing the need for a change, the Chalet’s new owners, former policeman and keen body builder Williams and martial arts exponent Mackey rebranded the Chalet as the Pacific Reef Resort. Ironically this writer, in my role as a graphic designer, created the new logo for the “resort”. In its optimistic marketing the Pacific Reef boasted “a newly decorated licensed restaurant suggesting a theme reminiscent of palm swept beaches and tropical ambrosia.” Guests were invited to “step back in time at the Western Bar to relax, meet new friends and enjoy the full bar facilities.”

The Western-themed bar was a contentious issue at the time. The bar at the Chalet, long popular with the local drinking subculture, was seen as a potential source of extra revenue but needed a makeover after the Ginn-McLeod era.

Riwai Williams remembers: “At first we had an idea of opening a bar for the locals with a Western theme due to the Mexican hacienda look that the bar already had. However the locals let us know strongly that they didn’t want this.”

For the next three years the Pacific Reef continued to operate as a restaurant and motel business, providing a venue for dining out, weddings, family functions and corporate events.

However district council zoning changes loomed on the horizon and Williams could see troubles ahead: “At this time the property was over an acre and I think the only property at Wainui at the time still zoned rural. When we got notice from the council that the property was about to be rezoned to residential we knew this meant a huge increase in our rates.

"After doing a subdivision costing we closed down the Pacific Reef as a business and began subdividing the property into seven (residential) blocks, one which contained the old Chalet building. This was sold to Don and Jenny Wilson as a private residence. Don and Jenny were caregivers from Hamilton, although Don was originally from Gisborne and used to play soft ball for Richardson’s Mill. The front set of units were sold and moved to Mangapapa and converted into flats. The units at the back I retained, had Taylors lift them and I renovated them into a private residence where my family and I lived for a further 18 months and then sold.”

When the subdivision work got underway Moodie as a mortgagee stepped in again and by the time the sections were sold off he was finally able to get his money back and say goodbye to the Chalet Rendezvous.

Moodie summarises: “Looking back over the ten years or more I was involved with the Chalet, well, it didn’t do me any harm. It gave me a lot of experiences I wouldn’t have had otherwise. When I first took on the second mortgage (with McArthur) my solicitor warned me about getting involved, he said I could lose everything. But I just dug my toes and went for it and eventually rode it out and at the end of it all I’ve come out all right.”

For a brief time the Chalet Rendezvous was

rebranded as the Pacific Reef Resort.

Neil Moodie is now 75 (that was in 2009 when this story was written) , retired and living at Whangaparaoa with his wife Shirley.

Malcolm McArthur worked in real estate in Auckland and later the Bay of Plenty. He died from a heart attack at Papamoa on October 28, 1997, aged 58. Annette McArthur still lives at Papamoa (at time of writing). Riwai Williams went to the United States to work as a long-haul truck driver. He then moved to Perth where hewas a supervisor of Transit Officers who manage the policing of Western Australia Public Transport Authority property. Taka Mackey went to Iraq to work in private security.

CHAPTER SEVEN: Backpacker lodge but the spirit lives on

Briefly in 1998 the Chalet was bought and used as a private home by Rotorua couple Donald and Jennifer Wilson. At this point, after the subdivision of the title, the remaining identifiable Chalet property had become just the road front section with the original chalet-style building. The Wilsons were IHC caregivers who, with children of their own, saw the former Chalet as an ideal place to look after a large extended family. Fourteen months later they sold the property and moved on.

Tony and Jude Harbott came to Gisborne from Dunedin in 1983. They lived in Russell Street for several years but when the opportunity arose to buy the Chalet from the Wilsons in 1999, which meant a shift out to the beach, they seized the moment. With five bedrooms upstairs and plenty of room for bunks down stairs they soon established the concept of a boutique backpackers lodge and so the Chalet Rendezvous morphed into the Chalet Surf Lodge.

On its website it was described: “Set by the sea and backed by the hills, the Chalet Surf Lodge has a range of accommodation facilities from unique backpackers accommodation to our lodge, where most of the rooms have a view of the Pacific Ocean and a large roof deck from which to catch the sunrise.”

The Harbotts ran the Chalet Surf Lodge for five years, it went so well they eventually became crowded out by the backpackers. So when another opportunity arose, they purchased the semi-completed house at the rear of the Chalet which was still owned by Riwai Williams. During this first period time with the Lodge they were regularly visited by the Kiwi Experience bus and other free and independent travellers making their way to Gisborne.

In a Gisborne Herald article from the time Tony Harbott said: “People had been asking what has been going on with the Chalet recently. Now it has new life offering funky accommodation to travellers from all over the world.”

Retaining the property at the rear of the Chalet Tony Harbott says: “It was a very special place, we loved it there and so many of the backpackers reckon it was the best place they’d ever stayed at.”

In September, 2004, they sold the seafront Chalet property to Jim and Nichole Rawls who continued with the backpacker concept until selling it on to Nicola Watkins in October of 2006.

That is where the story ended in 2009. 15 years on the Chalet is back in the ownership of the Harbotts and as of the summer of 2025-26, was still being run as an accommodation business.

Tripadvisor.com comments: "The location of this lodge is just perfect. It is situated a little bit outside of Gisborne. All you need to do is cross the road and you are at a perfect beach with superb waves. You can just grab a board at the lodge for free and enjoy the ocean. Nice owners."

And that is where we will leave it.