A Very Special Lady

The Life and Times of Muriel Jones

Written for Beachlife magazine in 2008

This story contains references to Muriel Jones still being alive. Sadly but inevitably Muriel Jones passed on in the summer of 2011. I am so glad that I was inspired and found the time to interview her and research the archives to provide this detailed account of her life and times which was published in the very first issue of Beachlife magazine in the spring of 2008.

Muriel's wedding. Duff and 21-year-old Muriel Jones at their wedding in Christchurch in 1947.

It would be hard work finding anyone who can keep up with Mrs Muriel Jones. She’s the little lady with boundless energy and a huge soul. The First Lady of Wainui Beach in every way. She has devoted decades of her time to Wainui Beach concerns and those of the wider Gisborne community. And at 82 years old Muriel Jones of Lloyd George Road hasn’t given up yet.

Older Wainui residents can only applaud and admire the selfless work Muriel Jones has put into her community over the years — and younger residents, who may not know too much about Mrs Jones, will be awed by her resumé of community positions and impressed by her determined and level-headed work for the empowerment of women over the last 50 years or more.

The first-ever woman elected to the Cook County Council was christened Constance Muriel Lance after her birth in Waikare, North Canterbury on the 26th of March, 1926. She was the first child born to Thomas and Meta Lance, who farmed at Horsely Down near Hawarden in the Hurunui District of North Canterbury. It was, at one time, one of the largest properties in North Canterbury.

“My parents lost the farm in the great depression, there were two lots of death duties during the 1920s and when a mercantile firm foreclosed on the mortgage in 1932 we were forced to give it up and went to Christchurch so my father could get work,” says Muriel. “I later came to understand the terrible trauma this was for my parents. They lost everything. They had to leave the country to start a new life in the city knowing they had lost the property that had been in the family for generations.”

With his skills as a farmer and a rural contractor Muriel’s father got work on the Waimairi county council in Christchurch driving steam engines and other machinery.

Muriel has two younger brothers and one younger sister. Her sister Susan, younger by eight years, still lives at Governers Bay near Lyttleton and they keep in touch regularly by phone and email.

Small town girl. Muriel Jones was born in the country village of Waikare in North Canterbury in 1926.

“I was six when we arrived in Christchurch in 1932 and went to the Fendalton Open-air School. I was petrified. I was so shy. I was the smallest girl at the school. I had grown up in the country, it was fairly remote, and I didn’t know any other children apart from my two younger brothers until I went to school.”

Two years later, to take up a contracting opportunity, Thomas and Meta moved to the settlement of Culverden on Highway 7 in North Canterbury, with the two younger boys and the new baby Susan. Muriel was left behind in the Christchurch suburb of Merivale with her father’s widowed mother, Mabel, and his sister Mildred, so she could continue her schooling. She later went to secondary school at St Margaret’s College and then on to University.

Muriel lived with her Gran, a dominating matriarch, and her spinster Aunt Mildred until the day she was married. They were good, church-going people, helping in the community, involved in charities and Church of England activities. They were friends with the local vicar who went on to become Bishop Warren of Christchurch. Aunt Mildred, known as “Mull” was a pioneer in the area of occupational therapy, teaching sewing and knitting in the Christchurch sanitarium.

The two older women were obviously a huge influence on the young Muriel, who went from child to woman under their watchful eyes. As the years went by the naturally shy but quick-witted country girl came out of herself and formed a great group of school friends making the most of Christchurch city life.

“My standard three teacher was W. J. A. (Bill) Brittenden, he made a huge difference to my life. (Bill Brittenen, 1910-1986, was a teacher, writer, historian, cricketer, city councillor. Writer Keri Hulme is another of his protégés.) He brought me out of myself and I became much more of an extrovert. I liked to be involved in things. I played hockey, swimming and later at St Margarets I took up basketball (netball these days). We had dancing lessons with the Christ College boys. At university I was involved in drama and rowing where I was the cox.”

Two men who played a big part in the life of Muriel Jones. At right is her primary school teacher, renowned academic of his time Bill Brittenden and, left, her husband Inovel 'Duff' Jones.

Muriel was thirteen when World War 2 broke out. By the end of the war in 1945 she was 19. Her’s was typical of a wartime teenage life lived through the early 40s, she says.

“ It was all very simple really. We used to go to Sumner beach. We knitted socks and gloves for the soldiers and made camouflage nets. There were shortages of things and rationing and we never missed a news bulletin, listening to the list of casualties. Apart from my godfather who was killed in Crete, we didn’t lose any of our family men-folk as they were involved in essential farming or manpower activities at home.

“Life was very simple in those days. We all had bicycles, there were no cars and we biked everywhere. Even later at university, after I had met Duff, even if we went to a ball, I went on the bar of his bike. Me in my ball gown and he in his dinner suit.

“Every school holiday I would go to stay with my parents in North Canterbury which I looked forward too very much. I was missing my little sister growing up, and the two boys, so I loved going home.

“The first time I was waiting for the bus, it went sailing past, and I missed it. From that time on I have had a phobia about catching buses, trains and planes on time. I am always early.”

In 1945 Muriel went on to the Canterbury College of the University of New Zealand, the forerunner of the University of Canterbury, still living at home with Gran and Mull.

Muriel had an idea to join the United Nations and an ambition to become involved in relief work overseas. To further that plan she embarked upon studying for a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in economics, political science and English.

Plans to travel the world, helping the poor and underprivileged were ambushed by a handsome man named Ionoval Ellice Jones who she met and soon became the centre of Muriel’s life.

Ngaio Marsh, well-known novelist and Shakespearian producer, was a friend of her grandmother: “Through Ngaio, Gran got me a part as a fairy in a university production of Midsummer Night’s Dream. Duff was the stage manager. That’s where we met.”

Ionoval Jones was known most of his life by the nickname “Duff”. An ancestor was a Welsh bard who’s two favourite places on Earth were the Ionian Sea and the Spanish Mediterranean city of Valencia. The two words were blended and became a traditional family name passed down through the generations. At the time he met his little Shakespearian fairy he was an engineer working for the DSIR, working on radar. As a can-do sort of bloke he also had a recreational interest in the technical side of drama and stage production.

“He was a handsome man. He was a capable, outdoors sort of man. Of average height with a great shock of brown hair. He loved fly fishing, bowls and golf. I thought he was the most wonderful man in the world,” says Muriel.

Muriel and Duff were married in 1947. Muriel was 21. It was a love affair but also a meeting of like minds. They were both university graduates, intelligent and capable. After the wedding they took a flat in Christchurch and at last Muriel was able to start a life away from Gran.

In 1948 they moved to Temuka, near Timaru, where Duff had been offered a job as assistant engineer with the South Canterbury Catchment Board in charge of river control and soil erosion.

In Temuka they were to stay for the next 14 years. Here they had their three children, Douglas, Diana and Elizabeth. Duff became involved in Rotary and was elected to the Temuka Borough Council. Muriel had three young children to take care of and became involved with kindergarten and plunket.

In rural Temuka in South Canterbury — known as the Angler’s Paradise, for its reputation for fine fishing rivers — Duff re-introduced Muriel, a country girl at heart who had grown up in the city, to the wonders of the outdoors.

“We were always camping somewhere, whitebaiting, fishing. Fly fishing around Temuka was brilliant. This love of the outdoors was to follow us to Gisborne, eventually, where we fell in love with Lake Waikaremoana and led me to play a role in local conservation.”

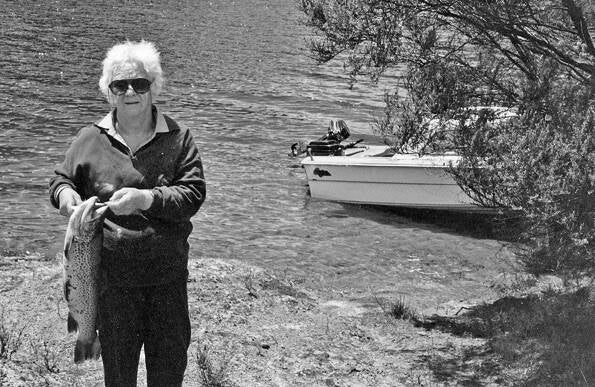

An outdoors woman. Muriel Jones with a 2.55kg catch at Lake Waikaremoana 1990 where they kept a boat moored and a permanent caravan set up at the camping ground at Home Bay.

In 1962 Duff was offered the position of assistant chief engineer with the Poverty Bay Catchment Board, at Gisborne. Muriel was not happy at the prospect of moving to the North Island: “Before we came we went to a family reunion in Hawkes Bay and Duff took me up Te Mata Peak. He pointed to the north to the hazy outline of Mahia Peninsula in the distance and told me Gisborne was as far away again. I said, ‘it’s the end of the Earth, I’m not going there’.”

But come north they did. They sent their furniture ahead, loaded up the Vauxhall, put the kids in the back and drove up to Gisborne. They rented a house in Bayley Street, Duff went off to grapple with his new position and Muriel went about finding schools for the children.

“I took Diana to Girls’ High where I met the head mistress, Miss Duff. In conversation she found out I had a degree in economics and political science. She said they were desperately short of qualified teachers and persuaded me to do an Emergency Secondary School Teacher Training Course.

“For the winter term I did relief teaching and by spring I graduated as a certified secondary school teacher. I had never intended to be a teacher, but I found I absolutely loved it. I taught at Girls’ High until 1975.”

So there she was in 1962, a fulltime teacher, wife, and mother of three school aged children. In 1962 that was not the norm.

“As a wife and mother I was expected to do everything that wives and mothers did in those days — as well as the job. Duff was supportive, but he wasn’t always happy. He didn’t like me marking exams at night for example, so I had to get up early in the morning to do that. It wasn’t easy.”

In 1970 the Joneses bought a section in Lloyd George Road at Wainui Beach. They paid $3600. They accepted a builder’s tender for just over $15,000 and started building a new house.

“It certainly wasn’t fashionable to build at Wainui Beach in those days. But we liked the idea of being self sufficient with water and sewerage, we loved the outdoor aspect, the beach.

“Our neighbours were Chris and Margaret Fenn, Doctor Joe and Doreen Costello, Bill and Colleen Vietch; all good friends. At one stage we had what we jokingly called the Lloyd George Ladies’ Surf Club. We had wooden flutter boards and we’d all meet down at the beach. I’m talking about Colleen Vietch, Diana Drummond, Molly Taylor. Neighbours all knew each other in those days. We had the church and later the community centre at St Nicholas Hall. If people were leaving we had a party and we welcomed new people.”

Muriel was in many ways, unwittingly at first, a pioneer of women’s liberation. It wasn’t intentional and she says she was never a radical.

In 1969 Pauline Cooper persuaded Muriel to join the Gisborne Business and Professional Women’s Club. By 1976 she was elected president. She was also greatly influenced by Frances Gregory, Gisborne’s first ever woman city councillor, and Peggy Kaua, a champion of Maori and women’s empowerment. They persuaded Muriel to become involved in the National Council of Women. She was elected local president in 1979.

“Frances had a huge effect on me, my mentor in so many ways. In 1977 I went to Christchurch for the national conference of the NCW, which was followed by the second Women’s Conference. It was the beginning of the women’s movement. I didn’t agree with the radical women there, they wanted to dynamite the whole system. I believed you had to join the system and work within it.

“Local elections were due to be held that year and when I came back to Gisborne from the conferences I was talking with Frances Gregory, who was about to retire from the council, outside the City Council offices when the then Mayor, Harry Barker, came out he said to Frances, ‘I’m sorry to hear you’re not standing for Council again’. Frances said, ‘I’m not, but Muriel’s standing for the Cook County’. And Harry Barker looked at me and said, ‘You have no right to.’”

“Well, that was all the encouragement I needed.”

That year Muriel was voted on to Cook County Council, the first female Cook County councillor in history. She was the only member who had to contest the election as all the others male councillors were reelected unopposed.

“They were all ‘good blokes’ and they just expected to get on again every year. I had two men against me each time I stood. I was on the County Council from 1977 to 83, and then again from 1986 to 1989. Then with the amalgamation of the county and the city I then became a district councillor from 1989 to 1995.”

During her time as a county and district councillor Muriel was the first woman to be appointed to the Urewera National Park Board. She also served on the Gisborne Employment Advisory Council, the Tairawhiti Community College Council and the East Coast National Parks and Reserves Board. She also help set up the Gisborne Citizen’s Advice Bureau and the Gisborne Council of Social Services.

“Rural local body politics in those days was really no place for a woman. Particularly on the Urewera National Park Board. We had to go on expeditions in the bush to look at things, and the men all used to sleep under an old fly with a fire at one end. I had to take along a little pup tent which I had to pitch a little way down the track.

“Later on we stayed in chalets by the lake. By then we all knew each other better and I would sleep in one of the top bunks. We called it mixed flatting.

“On field trips with the Cook County, at first they expected me to make the morning tea. I said, ‘No, I’ll open the gates, but I won’t make the morning tea.’ It was never easy. Some of them were so rude to me. But that was the climate at that time, it really was no place for a woman. There were very few women in local government.”

Muriel faced up to the prevailing chauvinistic attitudes, not by wielding the sharp sword of women’s liberation, but my using her natural intelligence and a belief in being prepared: “If something was coming up on the agenda, I would go and take a look at it and do my research. That was my only weapon, the power of being informed. To be effective I had to know what I was talking about.”

While Muriel pursued her political life and Duff was promoted to chief engineer at the Catchment Board, the Joneses continued their passion for trout fishing and the outdoors. They had a boat and a permanent caravan at the camping ground at Home Bay, Lake Waikaremoana: “It was our balance. We were very busy. Duff was also president of Gisborne Rotary for two years and then started Gisborne West Rotary and Rotoract for young people. We tried to get away to the lake as much as possible. It was an escape from our professional and public lives.”

Muriel Jones (left) with her inspirational mentors Peggy Kaua (centre) and Frances Gregory in 1995.

It was only twelve months after Muriel had been elected to the county council when Duff suffered a serious and debilitating stroke: “He was working over the road with Bill Veitch, we had a communal garden there. I was out canvassing for the council at the time. He was just 57. He was stopped in his tracks.”

Duff never recovered fully. He stopped his professional life and stayed at home, but was recalled for a time to help after Cyclone Bola. In many ways Muriel had lost her intellectual friend and political ally. They also had financial commitments and she had to keep working to make ends meet: “We still had a mortgage, I couldn’t just give up. I was an elected councillor and I was teaching part time, I just had to cope. But I was really lucky to have been involved in the community, being with people, making a difference, perhaps. At least I could come home each night, very tired and sleep well.”

Duff lived on, having several more smaller strokes, until he died in 1998. Muriel retired from the local body politics in 1995 after a heart operation. You would think that would have been a sign that said to Muriel: “Slow down, put your feet up, take a break from dealing with other people’s problems, look after yourself for a while.”

Not Muriel. After bowing out from district council duties, and despite the heart operation, Muriel waded in, sleeves rolled up, to do battle for a raft of community concerns. She became a member of the Gisborne Community Health Board; was elected chair of the St Nicholas Wainui Community Centre; made vice-president of the Gisborne-East Coast Multiple Sclerosis Society; became a board member of the Multiple Sclerosis Society of New Zealand; made president and later secretary of the Gisborne Stroke Support Group; became a member of the Medical Council of New Zealand Competence Review Committee; became a trustee of the Disability Information Centre Trust; became a distribution committee member of the Community Organisation Grants Scheme; became a support worker at the Stewart Centre for Brain Injury; became a life member of the Gisborne Cycle and Walkway Trust

To this very day she is actively involved as a member of numerous other organisations which include the Disability Support Advisory Committee; the Health of Older People Steering Group; the Positive Ageing Accord Action group; the GDC Disability Reference Group and there are probably others this reporter has missed — but you get the picture.

Numerous awards have come Muriel’s way. These have included a Suffrage Centennial Medal for Services to Women; a Rotary International Paul Harris Fellowship; a life membership of the Gisborne Stroke Support Group; a long service award from the New Zealand Stroke Foundation and a GDC Citizen’s Civic Award for her community work in general.

At 82 at her home in Lloyd George Road, surrounded by photographs of her life with Duff and her family, she is up early each day, on the computer, beavering her way through emails and correspondence from the various organisations she represents.

One of her main concerns still, is the well-being of the Wainui beach community. Although many of her old friends have passed away or moved to retirement homes, she is totally up with the play with what’s going on at the beach and is concerned for the welfare of all who live here. She watched with uneasy anticipation as the community fought against the proposal to reticulate. She knew she would be one of the “older people” who would not survive the rates increases. It worried her so much that her health deteriorated.

She is now elated that the unfairness and unsoundness of the proposal was exposed by the community and eventually rejected by Council.

“Wainui has had a rough deal all along. We have to pay the same rates as the city but we don’t get the same benefits. But the rejection of the reticulation proposal was the best thing that could have happened to us. Wainui can now look at the future and develop in an ordered way, instead off just slamming more houses on every half section.

“I think the landscape and planning assessment undertaken by Sue Dick will be great help in determining the future. It has recognised that this is a special place. It so easy to ruin these sorts of places, just look around the world, around New Zealand; Papamoa’s a classic example.

Why is Wainui so special?: “Because the people here, for the most part, are here because they love the environment. They’re not here to exploit the place or to make money from it’s continued development. If reticulation had gone ahead it would have been exploited, over-development would have been inevitable.”

Is that not attempting to make Wainui continue living in the past?: “No. It’s living in the future, because we’re future-proofing it. We have people here who want to protect the place and improve on the special qualities of a small New Zealand beachside community.”

So Muriel battles on. Her health is getting back to normal after the rejection of the reticulation proposal put her in hospital with a racing heart.

Friend and former fellow Gisborne district councillor Raey Wheeler, owner of the Odeon Theatre says: “Muriel is the kind of person who, when she takes on something, makes sure she does it right. She gets out in the community and makes a difference – she isn’t one to just sit around a table talking.

“She’s a wonderful person, she really has done so much for the community. And she’s a real family person. She adores her family. She was devoted to her husband Duff. She should be nominated for a really grand award. She’s still doing so much – I keep telling her to slow down.”

When Muriel does slows down she does it mostly in her beloved vegetable garden. She grows most of her own vegetables and gives lots away. She spins and knits. She reads. But she always has her meetings to attend.

“I still have a few crusades to fight. There are issues at the hospital. And since 1994 we have had plans for the Kaiti to Wainui Walkway and Cycle Track, and I’m still waiting. There are also various issues to do with disability and dangerous situations in the city for disabled people. I guess as I get older I start seeing things that aren’t right from the eyes of an older person. Often it’s just common sense.”

Muriel’s other great interest is her family. Her grown up children and, particularly, her five grand children and one great grand child. And, ironically, for a person who has devoted most of her life to the empowerment of women — they are all boys.

The young boys often come to stay for summer and over the years have brought their groups of friends. The house at the beach is often full and Muriel is seldom lonely. She goes to meetings, has numerous visitors and is a member of an informal “dining group” of friends who dine out at each others’ homes once or twice each week.

Saint Muriel of Wainui Beach? Well, this reporter thinks pretty much so. It is so uncommon in this day and age to meet someone so selfless, who works tirelessly and consistently for the well-being of other people, asking few favours in return.

And, at 82, where does she get the energy?