No Easy Escape

Rafters take chances on the Motu River in full flood

Written for New Zealand Listener magazine in 1982

This was one of the first major feature stories I wrote as a freelancer. The story was printed in the January 30, 1982, issue of The Listener. It was the story of a whitewater rafting trip I undertook with my brother Mark and a group of his friends down the remote Motu River, an adventure that came close to a disaster as the river rose to near record levels after an unexpected rainstorm in the Raukumara mountains. I took my camera down the river in an old army surplus ammunition box. The wildest, most dangerous descents of the river's fearsome rapids in full roar went unphotographed as we all hung on for our lives, trying to stay afloat in our old-school non-baling rafts as the mighty Motu flushed us down its gorges like corks in a maelstrom.

Deep in the canyon of the Motu our rafts are dwarfed by the magnitude of the cliffs that rise above the river. We soon learn that there is no way we could walk out from here, the only escape is to keep flowing with the river towards the sea.

Our party of 11 met the Whitewater Adventure Tours minibus at Opotiki on Saturday morning. Tour operator Brian Blewett shook our hands with his left. He later explained that he had broken two fingers on the Motu a fortnight before.

At 41, Blewett is an experienced outdoorsman. A former park ranger at Tongariro National Park, a member of the ski patrol and a St John's ambulanceman, he has now turned his attention to whitewater rafting. His partner is 23-year-old Dave Jordan, a lean young man who gave up the bakery trade for the taste of adventure. Together the two men have accumulated around $50,000 worth of equipment and have been making a living from the great outdoors for a number of years. So far they have taken 500 people down the Motu River.

"The Motu is really starting to be used for recreation now," says the quietly-spoken Blewett. "Hunters, rafters, fishermen – it's becoming more popular all the time. It's the only place in the North Island that people can experience a true wilderness river. It's a last bastion of isolated bush country. Entering the Motu is always a gamble. There's no easy escape, but that is part of its mystique.

After a 70km drive through the Waioeka Gorge to the small settlement of Matawai, we pull up to stock up on beer at the local hotel. "We don't mind taking booze on the river — but we have a firm rule that it is only drunk at night in camp. We also make sure all the empty cans come out with us," says Jordan.

We travel on, through the settlement at Motu, and stop to see the flow of water over the Motu Falls. The river is low, so to avoid a slow start we drive further down river through Waitangirua Station. It is not till early afternoon that we reach the Waitangirua River and begin to unload the gear.

Our sleeping bags, spare clothes and food are packed into large air-tight plastic barrels. We have two rafts – the smaller of the two becomes the supply boat. The barrels are stacked three high and roped down tight. We get into our wetsuits, put on lifejackets and helmets and suddenly. after weeks of anticipation, the 90km four-day voyage is about to begin.

Jordan calls for quiet and for the first time we look to the young man for authority. Our group consists of 10 businessmen from Gisborne the two guides and myself as photographer-reporter. There are nine on the big raft and five of us on the supply raft as we push off down the Waitangirua to its confluence with the Motu.

Taking photographs on a rafting trip means being in the lead raft and being prepared to clamber out onto the riverbank or a rock to get the shot of the main raft negotiating rapids behind us.

The Motu is still low and we have to manhandle the rafts over the first series of small rapids. It is fun, the sun is shining, the river is crystal clear – it looks like an easy trip ahead.

"People start off thinking this trip is going to be a Sunday drive,"says Jordan while teaching his new crew the various paddle strokes needed to propel the heavy rubber craft. "But they usually wake up by the second day. It is a fun trip, but we must never he complacent. The Motu is beautiful, but its isolation can he frightening and the treachery of the river keeps your adrenalin constantly flowing."

We come across our first pair of blue mountain ducks swimming up a shallow rapid, the first of many sightings of this rare species we make on the trip. Around a bend in the river we stumble across a herd of half a dozen deer crossing the river at the top of a small rapid. We hove to so the hunter in our party can take a shot, but his rifle's stock is packed away and he has to fire the gun like a pistol. The Motu thunders with the rifle's report and the unharmed deer scamper off into the dense bush.

We continue on our leisurely afternoon's journey, to Otipi Stream, about 25km down the river. It is an arduous task unroping the heavy supply barrels and manhandling them up to a shelf above the river, where we make camp – a huge sheet of black polythene on a ridge pole strung between two trees. Around the campfire, cooking food and drinking beer, we listen to the guides' tales of previous Motu descents. By comparison, our trip so far seems uneventful. We hope for a little rain to add spice to our adventure.

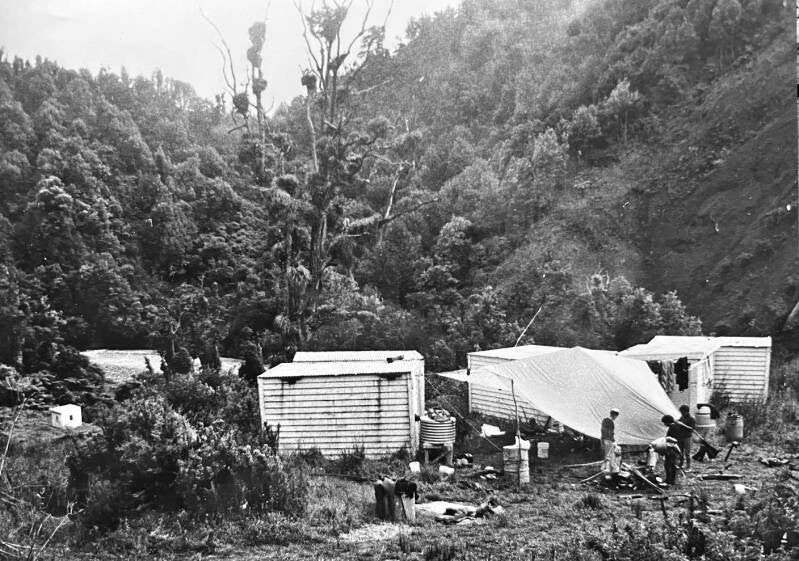

As the trip begins we get familiar with the strokes and moves necessary to steer the raft and keep it in the right place on the river. Dave Jordan (right) is the leader who has to form a solid crew with his eight paddlers.

The next morning's run takes us through virgin bush-clad ranges, the mountains rising out of the river on each side and disappearing into rain clouds forming high above. The first series of rapids are exhilarating, the rafts bucking through the crystal whitewater like rodeo horses. As we rattle down Bullivant's Cascade the rain starts to fall.

We are wet but happy as we pull up at the head of the next obstacle. Brian and Dave decide to portage our equipment over the rocks and pull the empty rafts through the rapid with ropes. Our problem is the cascade known as The Slot. Here the full force of the Motu is channeled into a fire hydrant of energy as it roars down a two-metre wide chute to a deep pool below. It takes over an hour to manoeuvre the first raft through the narrow causeway. By this time the rain is falling heavily and the river, crystal clear an hour ago, is turning muddy brown. And with each minute it is rising further.

Left: As the weather turns bad the river fills quickly and is soon bank to bank across even its widest stretches. Right: Our supply raft gets sideways in a narrow chute as the river rises by the minute.

The crew are dismayed at the idea of repeating the difficult operation with the second raft carrying the heavy supply barrels. Brian and Dave, with huge reservations, submit to our pressure and decide to try to paddle the raft with the aid of belaying ropes into a quieter channel to the left of The Slot.

Jordan is worried. Something tells him it is the wrong decision. But the older men, all owners and managers of businesses back in Gisborne, are persistent. We decide to try for the left channel. I volunteer to be on the supply raft with Brian Blewit as we start the manoeuvre. The rest of the crew are guiding us from the riverbank with a rope. I am holding on to that rope at the rear while Blewitt is paddling in the front. We edge across the river towards the opposite channel. We are almost there but suddenly reach a point where the suction of the Slot dominates the split current. I realise with horror that the only chance to avoid a plunge into the looming maelstrom is the thin rope I am holding and it is not tied to the raft. Its just me against the full power of the Motu. Stupidly I have the rope coiled around my left hand. It bites and tightens and I have just a split second before it fully grips and pulls me overboard. But I somehow narrow my handhold and the rope slides out of my grip. Then with the roar of a wild beast we plunge into the Slot.

We rocket down the first waterfall in the 50m long chute. Its narrow and I see a remote chance to save myself. I leap overboard off the back of the raft. I manage to grab the rocks underwater but I feel the current dragging me away. For a horrific moment I visualise myself being sucked backwards into the Slot behind the raft and its havy load of barrels. It's a traumatic moment that is frozen in my memory forever as someone in the shore party grabs my arms and I am hauled ashore.

Time freezes. Men stand like statues looking down at where the raft has jammed, upside down, under a torrent of thundering water. Brian Blewitt is nowhere to be seen. Suddenly, minds snap awake as hands reach beneath the foaming water and someone grabs a lifejacket.

Three men haul but Blewitt is stuck fast. The raft lurches forward and Brian's face emerges from the foam. Without a hint of panic, he quietly tells the men of the rope around his leg. He has been under the water for well over a minute. One of our party, Ray Moleta, has a diving knife on his person. He bends down on the rocks and feels for the rope. The rope is cut. The raft bounces on down the chute. Brian's leg was holding the entire weight of the raft, the equipment barrels and the entire furious force of the river.

He is hauled up on to the rocks. He rolls up his wetsuit leg to reveal his injury. The rope has ring-barked his leg almost to the bone.

In a matter of seconds our trip has changed. A dark cloud of uncertainty forms over us. Brian can hardly walk and the river is rising fast. It takes us a good hour to reinstate the rafts in the pool below the rapid and we push off into the current again. No one is laughing or joking any more.We now face the Motu with fear and respect.

Quick work with a knife by Ray Moleta most certainly saved the live of riverguide Brian Blewitt who was trapped in The Slot underneath the raft with a rope coiled around his leg.

The top image shows the split in the Motu River known as The Slot showing our intended route down the left channel that was thwarted by the strong current dragging our supply raft down the narrow right channel. The colour image shows a more recent British kayaking expedition on the Motu in a similar situation at The Slot.

Disaster strikes again only minutes later and a few kilometres into the Upper Gorge when the supply raft overturns and we lose all our supply barrels. Two men, including this writer, are swept down the river a way, using the technique shown to us to shoot a rapid when out of the raft. We manage to reach an eddy and claw our way up the bank. Three of us, including the injured Blewitt, have scrambled on top of a large rock in mid-stream. The raft is wrapped around the base of the rock they are stranded on. The barrels have been swept down river and can not be seen.

Myself and another rafter negotiate the river bank and make it back to the scene of the mishap. We realise that only teamwork can save us. After an hour of concentrated effort, with Blewitt giving directions, we have the raft righted and the crew back together.

With what paddles we can salvage, we let the river take us. We round a corner at the bottom of another rapid and come across the anxious crew of the main raft, who have miraculously managed to catch all our supply barrels and paddles as they came down with the current.

The river is by now seriously in flood, one of our guides is hurt, and we have lost our confidence. The rain we had hoped for the night before has turned our four-day adventure into a battle for survival with a raging river.

Despite the fear and anxiety we acknowledge that the gorge we are penetrating is awesome. On both sides sheer cliffs rise 400 metres above us. The forest high on the tops is lost in a swirl of mist. Every man is giving his full concentration to the job of keeping the rafts upright as the river takes us on a fierce rollercoaster ride through the narrow passage at the bottom of the Upper Gorge. And then suddenly we shoot between massive pillars of rock into the Mangaotane Valley and back to the first signs of civilisation in two days.

This is the site of the first dam proposed for the river and is our first real evidence of the government's interest in the Motu for hydro-electric power.

We have arrived at our campsite, which lies at the end of the Otipi Road, a track cut through the ranges by the Ministry of Works to reach the river in the 1950s. It is also the last potential escape route of our descent.

As our rafts are secured we sit quietly as the adrenalin subsides. We all know we have shared a unique experience; have looked death in the eye and escaped. I think of how close the rope came to ripping my hand off above the slot and what might have happened if I'd been swept under the raft in a tangle of ropes and barrels with Brian Blewitt.

Our spirits return as we make camp, light a fire and break open a fresh pack of beer. It is a relief to be out of our wetsuits and inside the Ministry of Works huts, which provide shelter from the teaming rain and the surrounding wilderness. Later we venture out to check the river gauge at the mouth of the gorge. The river is rising fast. The flood peaks at midnight after rising two metres.

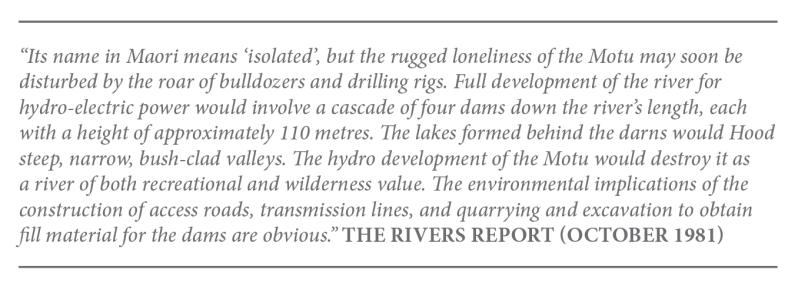

My late brother, Mark Clapham, jokeswith relief and earns a well-earned cigarette on arrival at Otipi Camp after the horrendous day on the river.

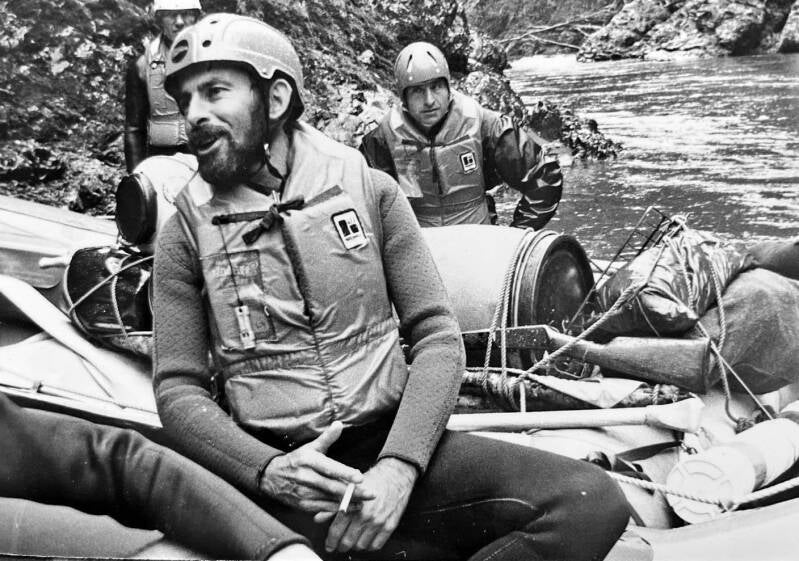

Safe and sound at the old Ministry of Work campsite after our descent through the flooded Upper Gorge. At that time in 1982 the campsite was a just a collection of dilapidated huts.

In the morning the rain has stopped and the river is slowly dropping. We are all apprehensive of the river ahead. Even the guides are unsure of the wisdom of shooting the rapids in the Lower Gorge tomorrow, but we have no option other than walking out via the Otipi Road. This no longer a group of businessmen on a fun weekend. It is now a group of men against a raging river. We know we must be alert and quick to obey the leaders' commands if we are to survive the next two days.

The river has dropped a metre by lunchtime as we make the decision to paddle away from Otipi camp and the our chance of escaping the river on foot. Quickly tht option disappears as we are swallowed by the wild, unforgiving landscape of the Raukumara ranges.

The river is bank-to-bank and chocolate brown. It no longer looks picturesque — it looks frightening. The current is swift and the high water level obliterates any obvious sign of rapids on this middle section of the river.

It is an exhilarating ride through huge misty valleys and by the time we stop for lunch we have regained our confidence and are enjoying the river's new mood. The river is flowing so fast that it is only an hour after lunch that we reach our next camp just above the Lower Gorge beside the Mangakirikiri Stream.

Three opossum hunters are well set up in the usual campsite so we cut a new clearing in a manuka stand on the other side of the stream. The opossum hunters are unsociable. Two refuse to talk to us; the other explains that they are "not too keen on people".

But he tellsus of two men who floated past on tractor-tyre tubes two days ago and another raft expedition a half a day ahead of us. The Motu is busy this weekend. We leave the opossum hunters to themselves and settle down to enjoy our last camp on the Motu.

A big feed of mutton chops and potatoes is prepared and we drink the best part of the remaining beer. Tomorrow we shoot the Lower Gorge — rapids like Double Staircase, Sonny's Revenge and Helicopter are waiting for us. As we crawl into our sleeping bags beneath the big fly-sheet stretched over a soft bed of fern it begins to rain again.

Our last morning in camp on the banks of Motu before tackling the rapids of the Lower Gorge. At this point of the expedition there was no other way out of the river running in full flood.

We are up early the next morning to find the river the same level as the day before. There is no way out but to carry on down the river. So at 7.45 am we push out into the current and are swept away into the Lower Gorge.

The rapids come before we have time to think. The rafts become corks in a huge washing machine as they hurtle down the rock-choked gorge. We fight to keep control as the Motu sucks us into a maelstrom current, creating swirling "keepers" that can hold a raft down and drown it in seconds.

The rapids come in quick succession. The run through the gorge is a blur of foam, crashing waves, looming rocks and the sensation of trying to stay astride a wild bucking beast. I submit to the river, not really caring if I am to be tossed into the waves to swim for my life. A feeling of calm pervades and I obey my guides paddle commands which are essential to our survival. Fear disspates. It becomes exhilarating. I am high on the river.

Then suddenly, the worst of the whitewater is behind us and we pull into the bank to bail out the flooded rafts. The frowns of the early morning have turned to smiles of victory. We have made it through; we have beaten the mighty Motu in one of its dirtiest moods.

With the panic of the rapids behind, we now have time to enjoy the river and take in the raw beauty of the country we are passing through. There are goats on the steep river banks and huge slips scarring the green hills from top to bottom. There is time to make jokes again and splash the crew of the other raft as they try to overtake.

Usually this last section of the river is a long slow haul, but we are travelling swiftly on the flood rushing to empty out into the looming Pacific Ocean.

All too soon the bush begins to change. Willows appear on the banks and suddenly the rough hand of man is revealed again where the hills have been cleared for forestry.

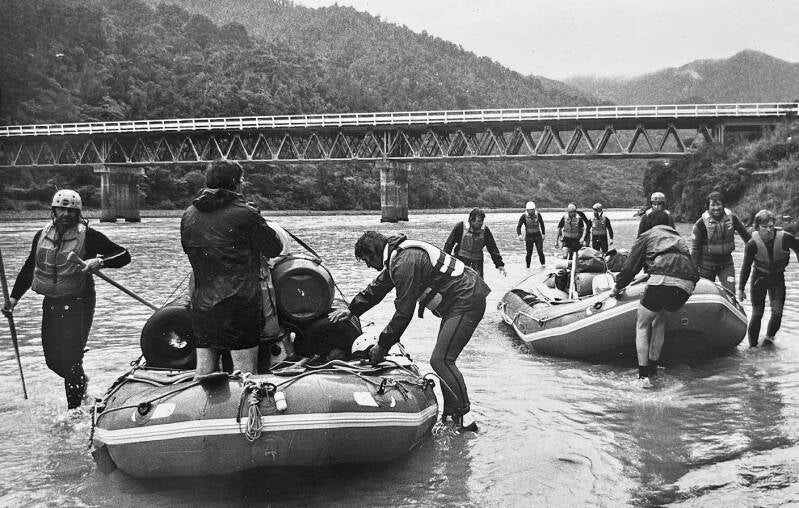

It is just after noon as we glide to final halt and deflate the rafts beneath the Motu River bridge on State Highway 35, just a few kilometres from the coast. The Whitewater Adventures Volkswagen arrives to take us back to Opotiki. With mixed emotions of relief and regret we pack up our gear and leave the Motu behind.

For the 45 years following this rafting adventure, those of us still alive who took part have appeared to share a special bond. Maybe a bit like men who have been through battle and survived. Even now, half a century on, we continue to acknowledge the experience whenever we meet.

Our four-day journey ends at the Motu River bridge on State Highway 35 in the eastern Bay of Plenty.