A Tale of Two Islands

Written for Beachlife magazine in 2011.

A family plays amongst the rocks between Sponge Bay and the two islands that existed at the northern entrance to Poverty Bay prior to the mining of the rock of the smaller island for reclamation work at the Gisborne harbour in the 1890s.

People are often fascinated to find out there were originally two islands off Sponge Bay, the rugged cove behind the northern headland that encloses Gisborne's Poverty Bay. For there was once a second island known as Puakaiwai between Tuamotu Island and the shore, which was completely obliterated in the late 1890s. As usual, thanks to the proclivity of turn-of-the-century photographer, William Crawford, there remains some black and white evidence of the lost island’s existence in local historical archives.

A brief archeological survey of the Sponge Bay area was undertaken in 2005 by the Department of Conservation which tells us existing Tuamotu is a small Island of approximately eight acres on the western side of Sponge Bay, or Papawhāriki, standing as a sentinel at the northern entrance to Poverty Bay, or Turanganui-a-Kiwa. It comprises a single principal ridge rising to 36 metres above sea level and two secondary spurs extending to the north and west.

The original shape and size of Tuamotu was significantly modified in late 19th and early 20th centuries by quarrying to provide landfill for the then developing Gisborne harbour. On Tuamotu the quarrying work has left a steep exposed face on the northwestern side of the Island and a low scrape on the north side of the Island.

Nothing remains of the landward second island, Puakaiwai. The two islands were once connected to the mainland, and to each other, by a reef shelf which was high and dry at low tide. This smaller island was quarried completely away. The rocky mass that was once its base still provides walking access to Tuamotu at low tide.

The demise of the tiny island began in 1872 when Gisborne was officially gazetted as a port and plans were sought for the construction of a deep water harbour. By 1882 a plan was adopted to create a breakwater to provide a sheltered deepwater entrance to the Turanganui River. The plan called for Tuamoto and Puakaiwai islands to be quarried to provide the necessary building materials.

After the Native Land Court awarded ownership of an area of land, known as the Papawhariki Block, to Hirini Te Kani and Edward Harris in 1886, the Gisborne Harbour Board obtained from the owners some three acres in Kaiti, five acres at Papawhariki (the mainland opposite Tuamotu) and the eight acres of Tuamotu Island itself. The land was taken under the Public Works Act 1882 and the Gisborne Harbour Act 1884.

In December of 1886 a six kilometre rail line was constructed connecting a storage, or block yard, at Kaiti on the east bank of the Turanganui River to Papawhariki and across an embankment over the reef to Tuamotu Island. The railway tracked along Crawford Road and through the gap that still provides road access to Sponge Bay, then along the base of the cliffs to Papawhariki.

Contractors began the job of quarrying the two islands, separating the hard rock from the softer material on the surface, and shunting wagon loads back to the Kaiti yard. Puakaiwai Island was entirely removed from the face of the earth during the early stage of the operation. It is thought the tramway to Tuamotu went underwater at high tides where the line branched to quarry faces on both sides of the island. It is estimated that some 67,895 cubic metres or rock was removed and transported to the port over a nine year period.

Fortunately, for the sake of generations to come, the quarrying stopped in the mid-1890s. The locomotive and wagons were withdrawn from service, the tramway was dismantled at Papawhariki with the old railway lines dumped on the foreshore to rust. The lines were removed from Crawford and Wainui roads in 1895.

However, respite was short-lived, for in 1905 the harbour breakwater was extended by a further 60 metres with the bulk of the stone coming from renewed quarrying at Tuamotu. This time a jetty was built on the island with the quarried material being transported by sea to the port in barges. The extension was completed in 1914 but further wharf development saw quarrying continue on Tuamotu in the early 1920s. Remnants of the jetty used in this era can still be seen at the island.

A recent view of Tuamotu reveals the footprint of what was once a second island that was mined for its rock which was used as landfill in the construction of the Gisborne harbour diversion wall. Precarious access out to the island on foot is possible at low tide.

A diminished and scarred Tuamotu was then left alone for several decades, visited only by intrepid rock fishermen and adventurous day trampers taking advantage at low tide of the remaining reef connecting the island to the mainland point, which had reverted to a marshy wilderness. However its peace was shattered yet again when, during the Second World War, it was used as a convenient target for bombing practise from the gun emplacement atop Kaiti Hill.

Today we can look at Crawford’s early pictures of the area with a certain sense of loss. Islands of any size touch something spiritual and primevally sensitive in most of us. But our nostalgia today must be insignificant compared to the loss the original Maori inhabitants of the area would have felt and their descendants may still feel.

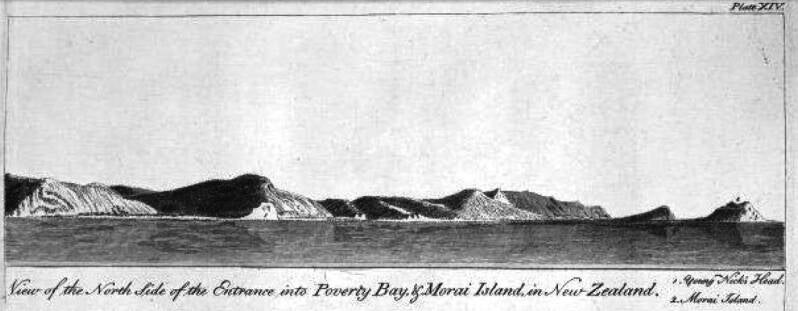

Tuamotu was an occupied island in pre-European times, established as a defensive pa. At the time of Captain Cook’s arrival, there was a stronghold on the island with a palisade seen atop its summit. Structures on the island were noted in Joseph Banks diary in 1769. Cook’s artist, Sydney Parkinson, included the two islands in a sketch of the area.

A Gisborne District Council report says at the time of Captain Cook’s visit the Ngati Oneone chief Rakaiatane’s son, Tuapaoa, lived on Tuamotu. It was his nephew, Te Maro, who was killed by Captain Cook’s sailors.

Captain James Cook's artist Sydney Parkinson sketched this view of the Poverty Bay coastline in 1769 which clearly shows the two islands off the northern headland of Poverty Bay.

An archeological survey of the island carried out in 2005 states: “The defended summit is relatively small in area and likely served as a citadel-type defensive position during times of threat, however extensive shell midden eroding from the southern terrace suggests it was permanently occupied. Probable storage pits and house floors are evidenced on the summit.”

The area was famous for its seafood, notably crayfish caught from the reefs, and paua. The coastal verge between what is now Gisborne and Wainui was a coastal thoroughfare utilised by several local hapu.

By the time the early European traders and colonists arrived, it is thought the island had become unoccupied. Trader J.W. Harris took control of the mainland at Papawhariki when he established a whaling station there in 1838. It is believed (J.A. McKay’s History of Poverty Bay) that he traded the land from its Maori owners for a “mare in foal”.

It was Harris’s son Edward Harris, from his marriage to Tukura, a woman of high rank related to Ngati Oneone chief, Rawiri Te Eke, and Te Eke’s son, Hirini Te Kani, who eventually saw the land pass into the ownership of the harbour authorities through the native land court machinations of the 1880s.

After the port abandoned its quarrying of Tuamotu in the 1920s the point at Papawhariki and the nearby island, although close to Gisborne city, became a neglected wildland due to lack of easy access. As the stretch of hills between Kaiti Beach and Tuamotu eroded, as did the beach from Sponge Bay to Papawhariki, steep cliffs fell directly to the sea and beach access became difficult. How much the removal of Puakaiwai accelerated erosion in the area can now only be guessed at.

The twin islands of Tuamotu and Puakaiwai can still be seen in this photograph by William Crawford not long after the commencement of mining operations on both islands in the late 1880s.

Adventurous Gisborne children found the wilderness of Papawhariki magnetic and this writer can remember a time when the flat land on the point was a series of marshy ponds which were explored by rafts built from driftwood. Seabirds built there nests there and children set up makeshift huts nearby. The reef, which was exposed at low tide, was a mine for Fools’ Gold. Sadly, a huge storm washed over the point in the 1980s and the wetland disappeared forever.

By a coincidence of nature the southern tip of Tuamotu forms a shallow, underwater, hammer-shaped, reef plateau with deep coves on each side. Ocean swells, on reaching the square head of this reef, rise out of the deep to create a cresting wave face that is second-to-none in this country. It was discovered by surfers in the early 1960s. Macho waterman of his day, Kevin Pritchard, is credited with being the first to ride the steep left-hand barrel that is today world famous and known as “The Bowl”.

Since then it has become a Gisborne surfer’s rite-of-passage to surf “The Bowl” in a big swell. There are other waves that break around the island including a right hander, “Outside Island”, on the other side of the reef that works in very big swells, and a fast left hander, “Inside Island”, that rifles down the rock-strewn side of Tuamotu adjacent to the former quarrying site on its western shore.

The long walk or paddle to get there, the size and steepness of the take-off, the dangers of the reef and a certain understanding that this was an arena set aside for “serious surfers only” kept The Island remote and almost mystical for decades.

More recent affluence, whereby surfers now often own boats and jet skis, means the location has become accessible to a wider group. It has also received its share of publicity in surfing magazines and has become a “must-surf” destination for travelling world surfers.

The surfers generally limit themselves to the island’s edge, mostly focused seaward watching for a lump in the ocean before it rears up from the deep to throw itself over the reef to slide steeply into the deep bowl behind. The steep land area of the small island is overgrown and wild, with a well-worn walking track over the southern plateau to the southern point where the surfers paddle out. Along this track is a life-size, carved wooden sculpture of a surfer, placed their by Wainui local and artist, Clayton Gibson, in the 1990s.

In 2005 Ngati Oneone, Tairawhiti Polytechnic, Gisborne District Council, Eastland Infrastructure and the Department of Conservation attempted to create a trust with the intention to reforest Tuamotu Island and provide a safe place for threatened plant species. However the project did not get off the ground for various reasons. The island remains in the legal ownership of the Gisborne Harbour Board.

Tuamotu is Gisborne’s only (remaining) true island. It has survived despite man’s best efforts to wipe it off the planet. It may be small but it has huge meaning to those who are attached to its pre-European past and also to those who appreciate its modern qualities as a surfing treasure. For these, and other reasons, 'The Island' deserves some latter-day love and respect.