A Passion For War

Written for Adventure magazine in 1993

After this story was written in New Zealand Adventure magazine in 1993, Gisborne man Terence White went back to Afghanistan where he photographed daily battles between the government and the religious militia and observed the rise and fall of the Taleban which culminated in his own near-death by a mortar bomb explosion in 1995. White later recorded the details of his injury and recuperation in his book, Hot Steel, named for the shrapnel that will be lodged in his body forever. He lived in Kabul, Afghanistan from 1992 until 1997, during which time he was employed by Agence France-Presse (AFP). He was expelled by the Taliban in 1997, though he returned after September 11, 2001 to cover the campaign led by the US to overthrow the Taliban regime. His most recent known status had him working as a full-time writer, living in Paris with his wife and two children.

A mujahid soldier mans a Russian-made anti-aircraft heavy machine gun in the Pansheer Valley of Afghanistan. Across his back is a Russian AK-47 rifle with underslung grenade launcher. The original photograph was taken and supplied by Terence White for the NZ Adventure magazine feature in 1984 from which this image in copied.

Terence White doesn't abseil. He doesn't ride a mountain bike. He doesn't get his buzz from whitewater rapids. White's idea of adventure is to sling a camera over his shoulder and to hitch a ride to the nearest war. For nearly two decades he has wandered through Asia and the Middle-East lured by the sound of gunfire. Merging himself with the ethnic culture he sides with, Terence White's style is to embrace the customs and the causes of guerrilla rebel fighters and to go with them into battle. In this way he has gained a unique journalistic perspective on the turmoil of our times. Here is a true photo-journalist, an adventurer to boot, in the purest sense. A man prepared to leave behind the comfort and security of home-town life, to burrow into hot desert sand to avoid the attentions of Soviet gunship patrols, to illegally cross borders to spend months living the life of a Muslim rebel freedom fighter, to risk his life to experience and document the tumultuous events of his time.

It was the family collection of National Geographic magazines which nurtured an early urge to see the world. After graduating from university in 1971 Terence White began the first of his endless travels. He set out for London, but was way-laid in the Far-East for nearly a decade.

His blooding as a photo-journalist came about by sheer coincidence. After two years of wandering through Indonesia and Borneo he turned up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaya, where he was accidentally involved in a Japanese Red Guard hostage shoot-out at the US embassy.

"It was an absolute fluke, all this shooting going on, I thought it was a bank robbery," he said. "I had my cameras with me at the time and when I was stopped by a security guard I bluffed them by saying I was a photographer with Associated Press, and was let through. It was the first time I was shot at. One of the Red Guards fired at me from an embassy window and the bullet hit the pavement at my feet. When the world press eventually descended on the scene the Bangkok bureau chief for AP caught up with me and said, 'So you're the guy posing as one of my staff, well since you're here, you may as well take pictures', and so that was my first assignment under fire."

It was 10 years before I wrote this story, back in 1982, that I first encountered a much younger Terence White. The Gisborne Herald daily assignment book directed me to the local art gallery where a home-town boy was showing an exhibition of black and white photographs titled: Portrait of Khao-I-Dang, Kampuchean refugees in Thailand.

The photographs around the walls of the gallery were stunning; a graphic documentary of the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge's five-year reign of terror in Cambodia. they were not the expected cliched images of suffering refugees. They were haunting images from the raw wound of man's inhumanity to man; a camera's insight into the suffering of a people subjugated by terror and oppression.

The photographer was obviously at one with these sorry people; for in the faces of these portraits of suffering and humiliation glowed an indelible dignity. I was intrigued by the photographs I saw that day and the man who took them.

The next day in the Gisborne Herald I wrote: "This exhibition is the repayment of a debt to the people of Cambodia. Terence White,32, left home nearly 10 years ago and has spent the past decade traveling in Asia. Terence White wants to share, through this photographic documentary of his six-week stay in the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp in Thailand, an emotional experience second to none he has had before. This exhibition of black and white prints is more than an artistic dabble in South East Asia; it is a moving historic documentary of one of the biggest cultural upheavals in modern times."

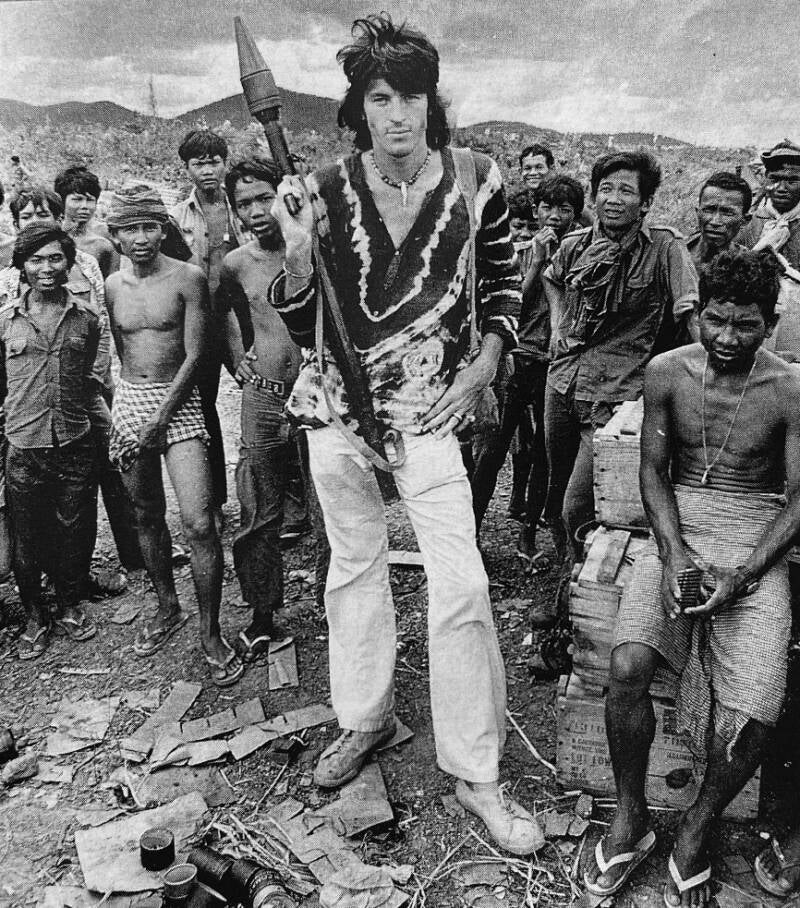

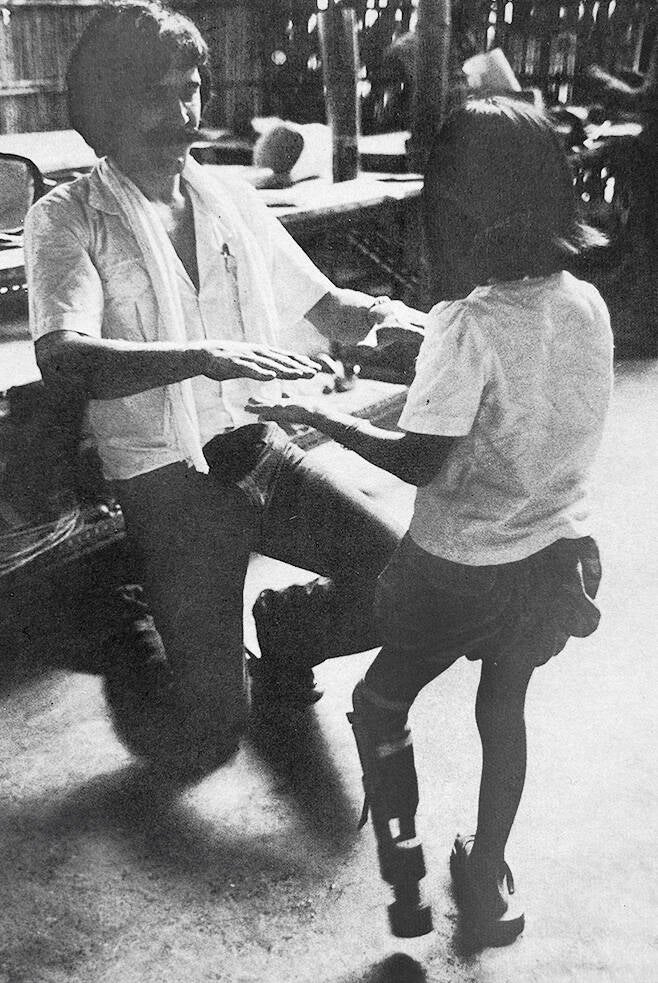

LEFT: Terence White, then 32-years-old, poses with a captured Chinese-made grenade launcher in Cambodia in 1984. RIGHT: A young land-mine voctim is fitted with a prosthesis by a French aid worker at the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp on his first visit to Cambodia in1980.

After the exhibition Terence White stayed around Gisborne for a short while. But he couldn't settle back into home-town life and had soon packed his cameras and fled; back to the front-line with a thirst for more adventure.

For the next decade photographs and feature articles by Terence White appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers around the world. In 1984 I read an illustrated report in the Listener of Terence White's excursion into Kampuchea with soldiers of the Khmer Peoples' National Liberation Front. A year later another news report, this time from the Hindu Kush in northern Afghanistan, where Terence White had attached himself to the mujehadeen guerrilla forces fighting their Soviet invaders.

There was a report in the Far Eastern Economic Review on heroin trafficking in Pakistan; an account and photographs in Newsweek, again from the guerrilla conflict in Afghanistan (all told Terence White went into battle 10 times with the mujehadeen).

In later years he made his own headlines after being jailed in Thailand and later deported for an assignment he undertook into south-east Asia's 'Golden Triangle'. He illegally crossed into Burma to attend a 'press conference' called by Thailand's most wanted man, the opium warlord Khun Sa. However, Terence White maintains it was not the border crossing, but the political embarrassment he caused that led to his falling out with the Thai government.

There were reports of his involvement with the Tamil Tiger rebel forces in Sri Lanka and during the last few years of the '80s Terence White was back in the mountains of Afghanistan with his mujehadeen 'brothers'.

As a journalist I have always harboured a respect for, and an envy of, Terence White. For in a disarming and cavalier fashion he embodies the premier requirement of photographic journalism; the not-so-simple art of 'being there'.

He has no formal training in journalism, is self-taught in photography (his Bachelor of Science degree with honours from Auckland University in marine biology has little relevance when deciding on shutter-speeds during a missile attack) and makes very little money from his adventures.

But in spite of a lack of official credentials he has repeatedly placed himself at the frontline of the power struggle of the '80s and has returned with the pictures to prove it.

For this striking man (he stands 6 feet 6 inches tall – a family trait, he is a nephew of the great All Black line-out master Richard 'Tiny' White) – has the ability to immerse himself in the culture of the people he seeks to document.

"After a while they know me as a person and treat me as one of the family. Sometimes there is suspicion of journalists; they have little understanding of news in the western sense. I have empathy with the people, in many ways I become one of them, and observe their customs. I eat their food, live and dress as they do. I put up with the hardships and don't expect any special treatment. Some journalists set themselves apart from the people they are involved with, but I get into the whole scene and they can sense that."

Terence White photographs a mujehadeen firing an RPG-7 rocket launcher in an attack on an Afghan communist security post near Kandahar in Afghanistan 1989.

On his travels he has picked up an under-standing of numerous languages—enough to get by on in Malay, Indonesian and Farsi (Iran and northern Afghanistan) and a smattering of Thai and the Khmer language of Cambodia.

After the Red Guard incident in Kuala Lumpur in the early 1970s he went to Cambodia and then hitched a ride on a US arms convoy down the Mekong River to Saigon where he spent six weeks traveling about war-torn Vietnam. Back in the Cambodian capital of Phnom Phenh in early 1985 he worked with an American relief agency, often under fire, as Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge advanced on the besieged city.

When the fall of Phnom Phenh became imminent he was airlifted out of country in the scramble of evacuation with fleeing Cambodian government officials and US diplomatic staff. Later in Laos, when taken for an American spy, he brushed with death before a communist Pathet Lao firing squad, but was saved at the last minute by the arrival of neutral forces.

By 1976 he had traveled overland through India and Kashmir to arrive in Iran with $US10 in his pocket. Here he taught English for a while until forced to flee when the Shah was overthrown by the fundamentalist revolution inspired by the Ayatollah Khomeini's return from exile.

From his two years in Iran he took to Paris a collection of photographs on the plight of the Kurdish nomads in Iran. Friends urged him to take his photographic journalism more seriously. "By this time I had fallen in love with both traveling and photography—the obvious choice was to combine the two and work as a freelance photo-journalist."

He approached the publishers of German GEO and headed off to do a speculative feature on an exotic tribal people of a north-eastern state of India. But by now Terence White was discovering he had a fatal attraction to drama and intrigue. A politician was assassinated while he was there, torn apart by machine gun fire, and Terence White was the main suspect, implicated also as an illegal arms dealer. As the Indian Special Branch descended from New Delhi he fled back to Thailand.

There, a chance meeting with an old friend from Iran led the photographer to the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp on the Cambodian border. Here Terence White spent six weeks documenting the carnage the Khmer Rouge regime had caused in the five years since he had fled from Phnom Phenh.

It was these photographs he arrived home with to exhibit at the Gisborne Museum and Arts Centre in 1982.

Terence White admits, without apology, that he is intrigued by the events of war and weaponry. But he chooses to carry a camera rather than a gun into theatres of conflict.

"In 1974 I hitched a ride as a tourist to the temple ruins of Angkor Wat in Cambodia; I also stumbled into a war, my first. My reaction wasn't repulsion, but fascination. Since then I've been hooked on it; war is a kind of addiction. There's an off-beat glamour to war which is part of the appeal to me. In many ways photo- journalism has been an excuse to get involved.

"Observing war, even participating, becomes more important than recording and reporting. In the early days the buzz, the emotional charge of being there, was more important than the money. I've changed a little now. Now, I'm more aware of the commercial potential of any project I undertake, but the bottom line is that journalism gets me to where the action is!"

As this article was being written (in 1993) Terence White had been home in Gisborne for 18 months and had completed a book about his time with the mujehadeen in the closing months of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan. He then departed for London to follow up publishing possibilities. After that he faces a dilemma. Where next?

Iraq, Croatia, the unfolding drama in the Soviet Republics? With revolution exploding so quickly around the trouble-spots of the globe Terence White has to respond quickly to the sound of distant gunfire to satisfy this passion he has for war.

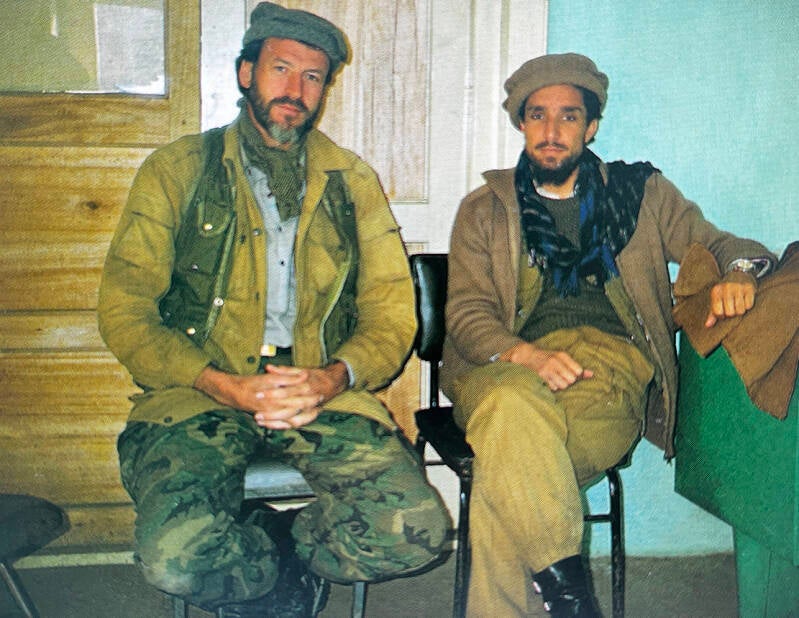

With his dark looks and imposing height, Terence White (left) was able to blend in with the Afghani people who named him 'Safed Khan'. In this image taken in 1989 he poses with Ahmad Shah Massoud, also know as 'The Lion of Panjsher', the most renowned of the Afghani mujahideen fighters.

23 years after this story was written I caught up with Terence White

at the Gisborne Farmers' Market on New Years Eve day of 2016.

NOTE: Since we last caught up in 2016 I have lost touch with Terence White. His online footprint is small and searching gives virtually no indication of his whereabouts or circumstances today. If by chance you read this story Terence, or anyone who knows of Terence, please drop me a note at gray@fadetogray.co.nz.