A Dive in a Duckpond

A travel adventure to the top of the South Island

Written for Signature magazine in the 1990s

In the mid 1990s I turned my hand to writing the odd travel story, most often in the company of my incorrigible adventure and outdoors photographer friend and mentor Gareth Eyres, who I had met while working on Adventure magazine which was published by our mutual friend John Woods. Gareth was New Zealand's photographer of the moment at this time, particularly with the New Zealand Tourism Board, and he would often call me up to accompany him on assignments where he needed someone to be the "model" for his pictures, write a story, or just for the company. On many of these occasions, I saw the opportunity to make a buck of my own by writing stories about our escapades. This story was published in a short-lived travel magazine called Signature (Diners' Club) which was happy to accept my offerings.

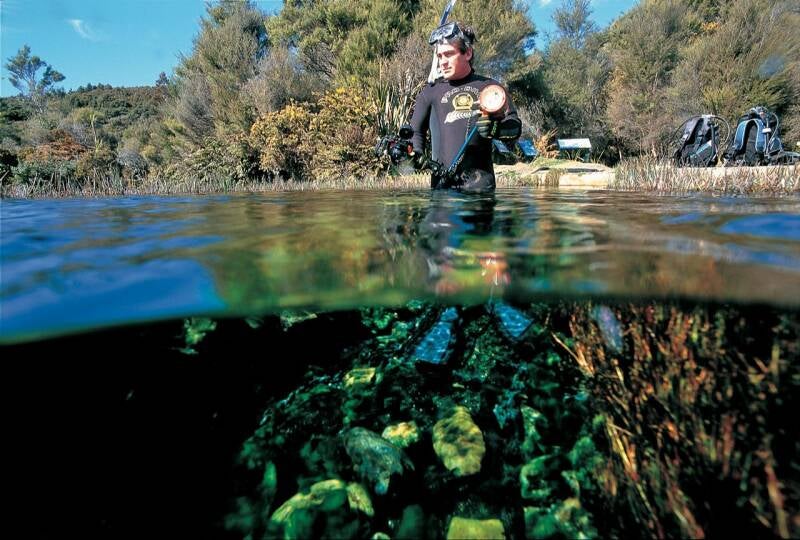

The writer photographed scuba diving in the duckpond, also known as Te Waikoropupū Springs located in the Tākaka area in the Nelson-Tasman region. It is famous as the largest freshwater springs in New Zealand, the largest cold water springs in the Southern Hemisphere and reportedly the clearest water ever measured anywhere in the world. At the time you could dive in the springs with DoC permission.

My friend the photographer had a plan. "Would you like to come diving in a duckpond?" he emailed. "Of course I would," I replied without deliberation. "When do we leave?" I never say no and seldom question Gareth Eyres' travel plans, for over the years I have learned that travel with Eyres is by no means boring, let alone predictable.

We rendezvoused in Nelson, procured dive tanks, then drove on to Motueka to find a meal and beds. The expedition to dive the duckpond would be timed for mid-morning the following day, when, hopefully, the light would be optimal. I learned we were on assignment for an international dive magazine, and I was the model.

Motueka, 40 minutes west of Nelson and adjacent to the tidal mudflats of Tasman Bay, was once famous for its tobacco. The evening we arrived it was famous for its exploding Volkswagen. The Nelson Mail ran the story of Motueka identity, Bill Ayers, whose Volkwagen had exploded into flames as he travelled down King Edward Street the day before. "I just heard a loud bang and there were flames everywhere," Ayers, the owner of a local recycling plant, was quoted as saying.

The demise of the tobacco industry in the district is still a bitter pill for the people of Motueka to swallow. Like many small New Zealand towns which have lost their traditional industry bases, Motueka is now promoting tourism. Eyres and I thought an annual Exploding Volkswagen Festival would be a novel attraction. Motueka, population 12,000, has been struggling to find new raisons d'être after the removal of government subsidies and the closure of the Wills cigarette plant saw commercial tobacco cropping come to an end in 1995.

The closure of another local industry provided our beds that night. Bakers Lodge was formerly Goodman's Bakery, which closed in 1996. In line with the town's new push towards tourism it was renovated and reopened in 1998 as a budget-priced accommodation complex.

The morning saw us driving in warm spring sunshine through the Riwaka Valley's bucolic landscape of former tobacco farms, hop fields and apple orchards, then up and over the infamous 952-metre-high Takaka Hill that, in days gone by, would cause cars to boil their radiators.

Leaving behind the hill's jagged-edged marble-kaast landscape, we coasted down into the Takaka Valley, as beautiful and rustic a valley as you could find anywhere in New Zealand, and followed the Takaka River into the town of the same name. Just a few minutes more up the road beside the Waikoropupu River and we pulled into a car park at the duckpond.

A duckpond it may be, but Pupu Springs is the clearest duckpond in the world. So clear that it is world famous, and the reason why an international dive magazine wanted pictures of someone diving in it. We kitted up and waddled the 500 metres or more along the narrow bush-lined track to the main viewing area in full-length dive suits, with tanks on our backs, weight belts strapped on, masks, snorkels and flippers, and a huge bag of assorted underwater camera equipment.

It was with great relief that we finally slid into the chilling 11.7°C waters of Main Spring in the 130-metre-wide pond called Pupu. Main Spring, a natural aquarium of various aquatic plants and weeds, is just under seven metres deep and not much wider across. Only four divers are permitted in the water at one time, and even that is a crowd.

What makes it even more interesting is the speed and the amount of water that gushes from its underwater vents. The total flow of water into Pupu averages around 14 cubic metres a second – that's 40 bathtubs full each second. In Main Spring, there are eight vents, each of which cause sand to geyser, rocks to dance and divers to be tossed like moonwalkers.

Being a conservationist at heart, I self-debated the ethics of my wallowing around in such a pure and fragile environment. Swimming is not allowed in Pupu Springs, but tank diving is. There is a consultant's report due out very soon that may decide the future of diving and other issues being debated about Pupu's management. The way to make the most of Pupu without damaging things, I discovered, was to relax and be a totally passive observer. To avoid touching anything while drinking in a symphony of colours and textures amplified and enhanced by the crystal-clear water.

Eyres said the visibility in diver's terms was 300 feet; in duckpond terms it meant you could have viewed a duck's bum nearly a hundred metres away.

Inside the metre-wide cavern of the main vent, a lone salmon rode a treadmill to nowhere against a rush of outflowing water. That same water may have spent up to a decade filtering through a labyrinth of underground limestone drainpipes originating some 10 kilometres inland, where the Takaka River disappears beneath its own gravels. On its subterranean journey to find the sea, it travels beneath an impermeable lid of rock and mudstone to emerge, filtered and pressurised, through faults in a thin layer of the lid at Pupu.

Only a portion of this underground river (said to be twice the volume of Lake Rotorua), breaks out at Pupu. The larger portion flows into Golden Bay via submarine springs.

After exiting Main Spring and humping our cumbersome equipment back to the car park, we decided we needed something a little more boisterous to complete the day. We found someone to ferry our car a kilometre or more down the road to the Pupu Bridge, and then with snorkels, masks and flippers flopped into Fish Creek, the shallow stream that drains the springs, and embarked on a 20-minute drift-dive with the current. Like fat black eels we swam underwater, squirming over shallow rapids, dodging snags and generally relishing the submarine perspective of a clear flowing river.

It was with great relief that we finally slid into the chilling 11.7°C waters of Main Spring in the 130-metre-wide pond called Pupu. The total flow of water into Pupu averages around 14 cubic metres a second. There are eight vents, each of which cause sand to geyser, rocks to dance and divers to be tossed about like moonwalkers. When this story was written four divers were permitted in the water at one time under DoC regulations. Today visitors are allowed to view the springs via a boardwalk but cannot even touch the water.

On the way back to Nelson the next morning Eyres said what might be rather nice would be a glass or two of the region's most famous wine. In a country as small as New Zealand it is slightly quirky that there should be two famous people called Tim Finn. It was famous Finn the winemaker that we shook hands with on his six-hectare Neudorf Vineyard.

Eyres went about his photographing across the wide, manicured lawn as I sat down on the patio under a trellis of overhead vines to try a pinot noir, soak in the old-world, oak-tree-shaded Neudorf surroundings and attempt to talk intelligently to Finn. Finn is a much renowned winemaker with a very intellectual approach to producing wines from the low-yield vines he carefully nurtures on the rough gravel and clay soils at the bottom of his garden.

What I believe I gleaned from talking with him was that it is all to do with "terroir" – a French expression that attempts to describe in one word the climate, the soil and the passion of the winemaker. The "terroir" at Neudorf must be exceptional, for the vineyard is recognised as one of the leading New Zealand wineries' producing pinot noir, riesling and sauvignon blanc, and is considered by many to make the best chardonnay in New Zealand.

I asked Finn what I should be looking for in a good chardonnay these days. I might as well have asked Van Gogh to explain the essence of landscape painting, for Finn took me on a word journey into the world of winemaking that I can only describe as passionately poetic.

Although I knew I was way out of my depth, I came away with the overall impression that successful winemaking (and in turn wine drinking) is not so much about reaching an ultimate and predetermined concept of success; but rather, like art itself, an endless journey of creative expression that has no ultimate preconceived destination.

Full of such oenological thoughts, we turned towards Mapua on the coast with ideas of a seafood lunch. At the Mapua Wharf, looking out to the yachts moored in the estuary, we sat down to sample the cuisine at Mapua Nature Smoke Café. Built around an on-site smokehouse and run by Tom and Vivienne Fox, this relatively unique dining concept has become a Nelson success story due to its fabulously fresh seafood and its picture-perfect location.

Eyres and I had a smorgasbord-style platter of wonderfully tasty items—a variety of different smoked fishes and shellfish—which we washed down with a glass or two of Finn's finest.

In the pleasant Nelson sunshine we ruminated about the 40 bathtubs a second of amazingly clear water that issues forth from the ground at Pupu and the debate over its accessibility and conservation, about the elusive qualities of a good chardonnay, about the troubled economy of Motueka and about exploding Volkwagens. I concluded that, like travelling with my friend Eyres, nothing is predictable and nothing is permanent; and that, in essence, is the wonder of it all.

Note: When this story was written four divers with tanks were permitted in the water at one time under DoC regulations. Today visitors are allowed to view the springs via a boardwalk but cannot even touch the water.